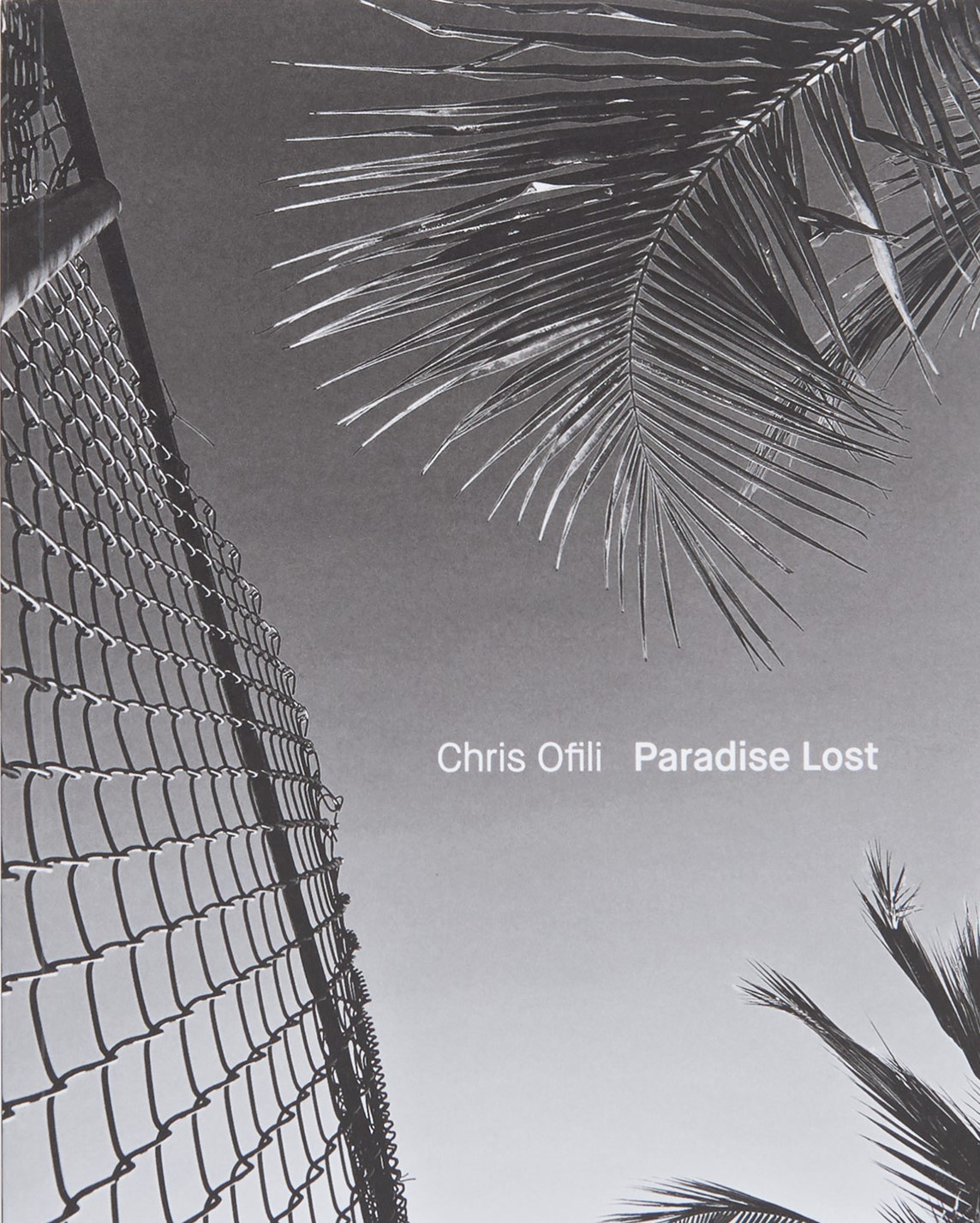

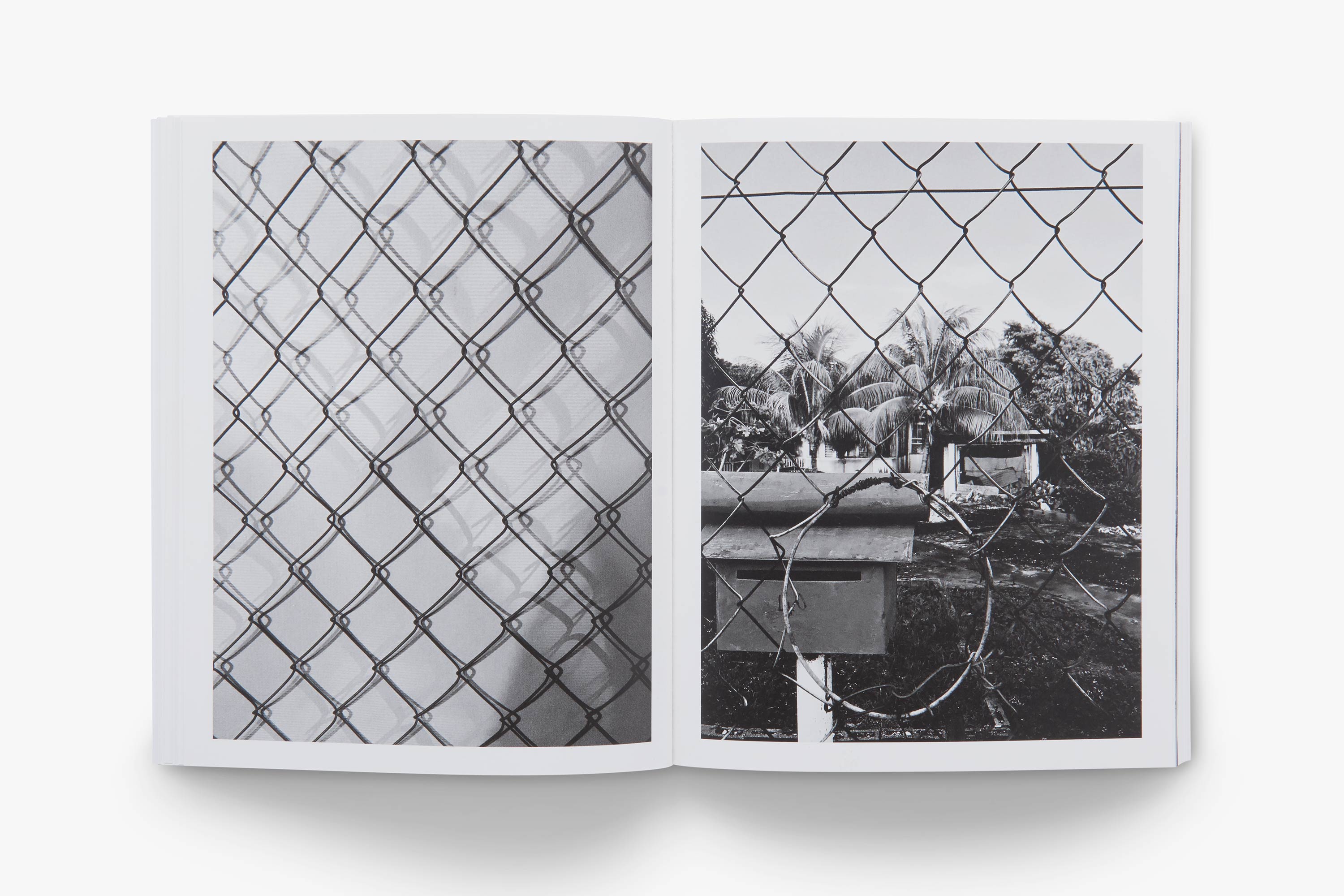

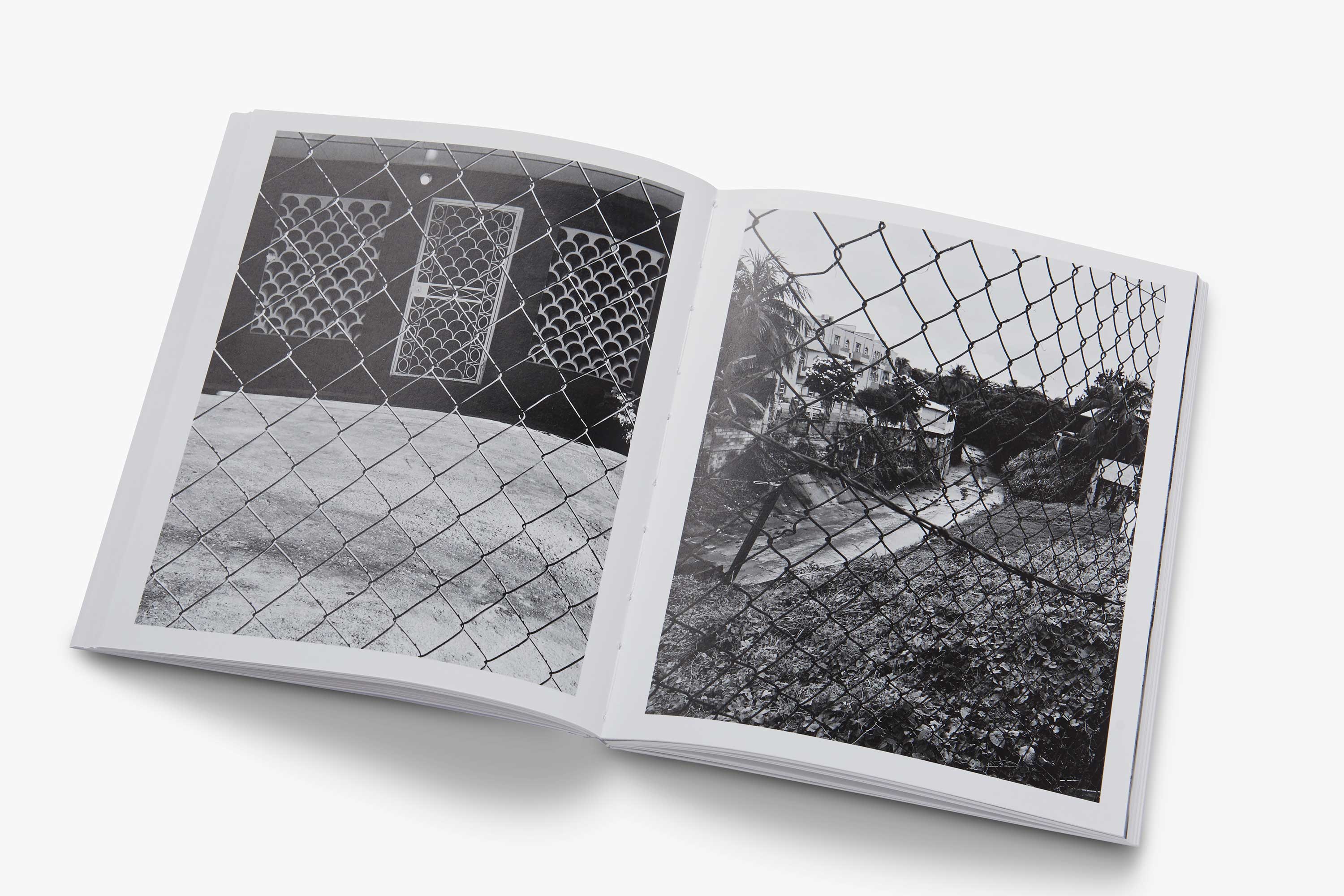

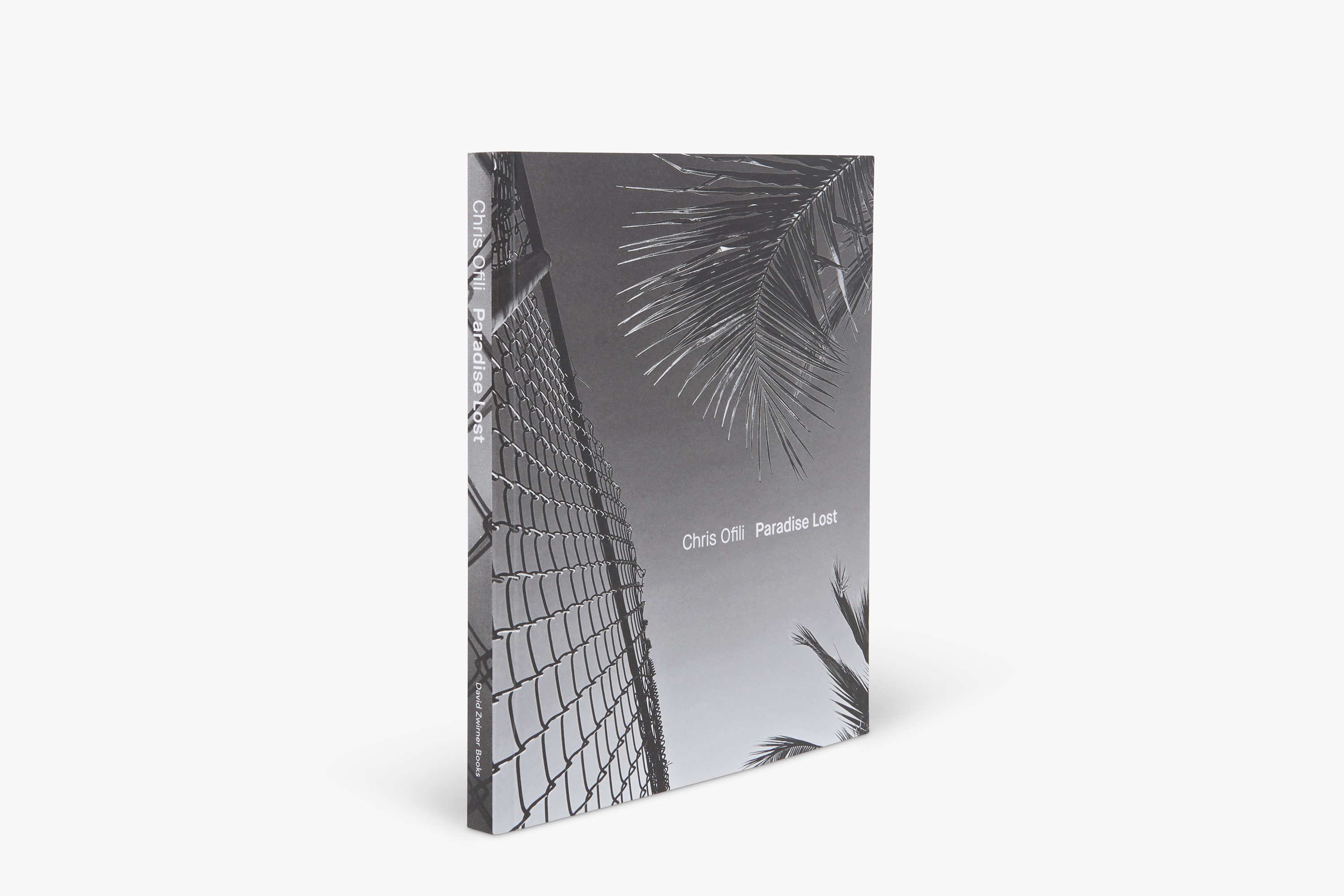

En 2017, Chris Ofili a photographié des clôtures grillagées dans toute l’île de Trinidad afin d’explorer les notions de beauté, de communauté, de libération et de contrainte. Cette série d’images saisissantes – « photographie de poche », telle que décrite par l’artiste – est le premier corpus photographique jamais publié par Ofili. À travers ces photographies en noir et blanc, l’artiste s’engage avec les diverses sources qui ont inspiré son exposition Paradise Lost, acclamée par la critique, à la galerie David Zwirner (New York), à l’automne 2017.

Depuis son arrivée à Trinidad en 2005, Ofili a continué à s’engager avec l’environnement et la culture environnants, qui a trouvé son chemin dans beaucoup de ses peintures colorées. Dans ces photographies en noir et blanc d’une simplicité trompeuse, il capture une large section transversale de Trinidad en mettant en évidence la rencontre entre les milieux naturels et artificiels, et les différentes possibilités esthétiques que chacun apporte à l’autre. En se concentrant sur une pièce d’équipement omniprésente et apparemment banale, Chris Ofili est en mesure de commenter nos interactions avec l’espace et les uns avec les autres, en utilisant un sujet quasi universel que la clôture tranche le ciel, se mêle à un arbre, encadre un match de basketball ou révèle une ouverture.

Dans un nouvel essai de l’auteur acclamé par la critique de Island People : The Caribbean and the World (2016), Joshua Jelly-Schapiro retrace l’histoire des clôtures à chaînons, en se concentrant sur une sélection de photographies d’Ofili, il commence ensuite à explorer ce que cette imagerie nous dit de Trinidad en particulier et des Caraïbes dans leur ensemble. Ces deux essais — l’un visuel, l’autre littéraire — ouvrent la voie à un tout nouvel ensemble de possibilités d’interprétation pour cet artiste novateur.

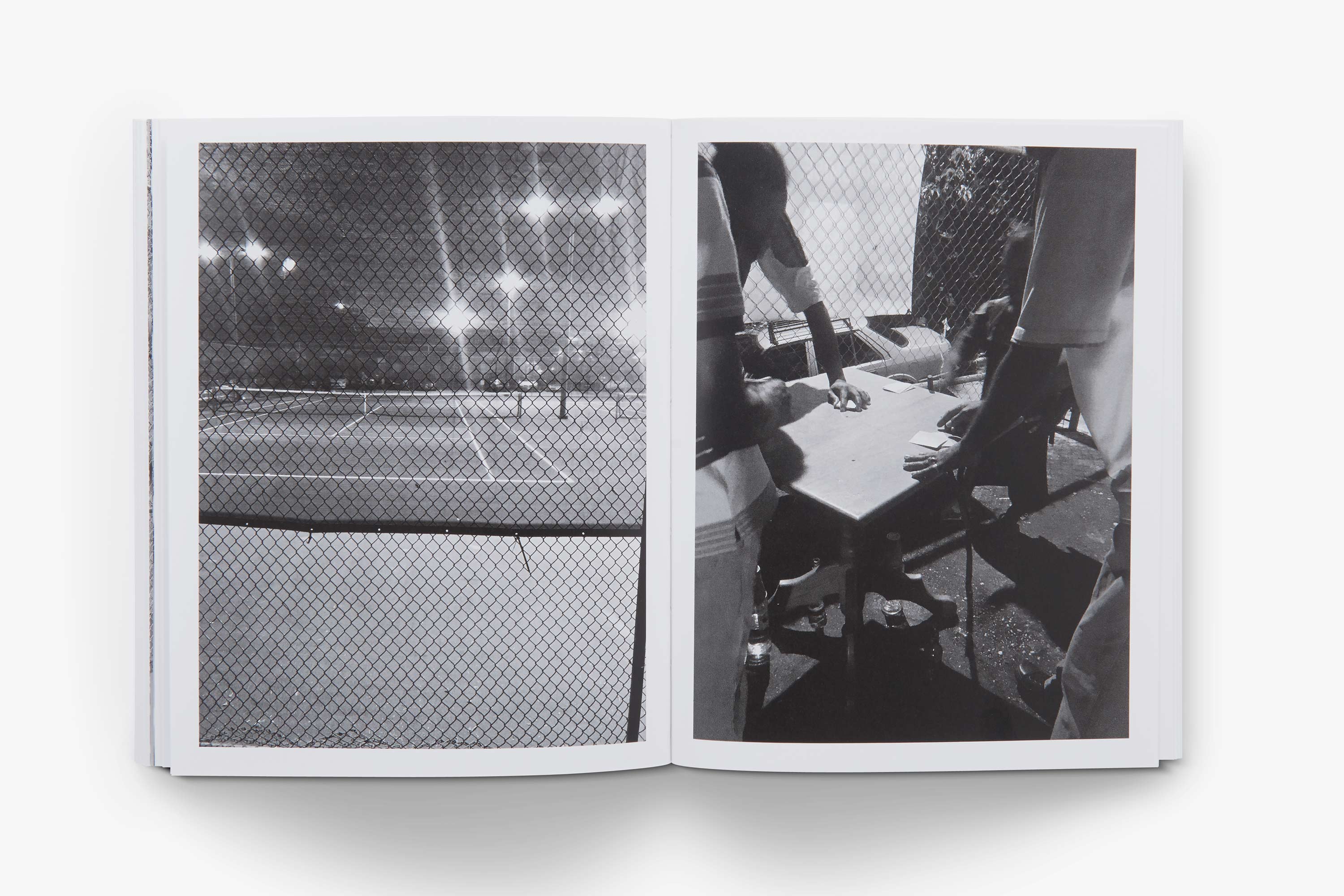

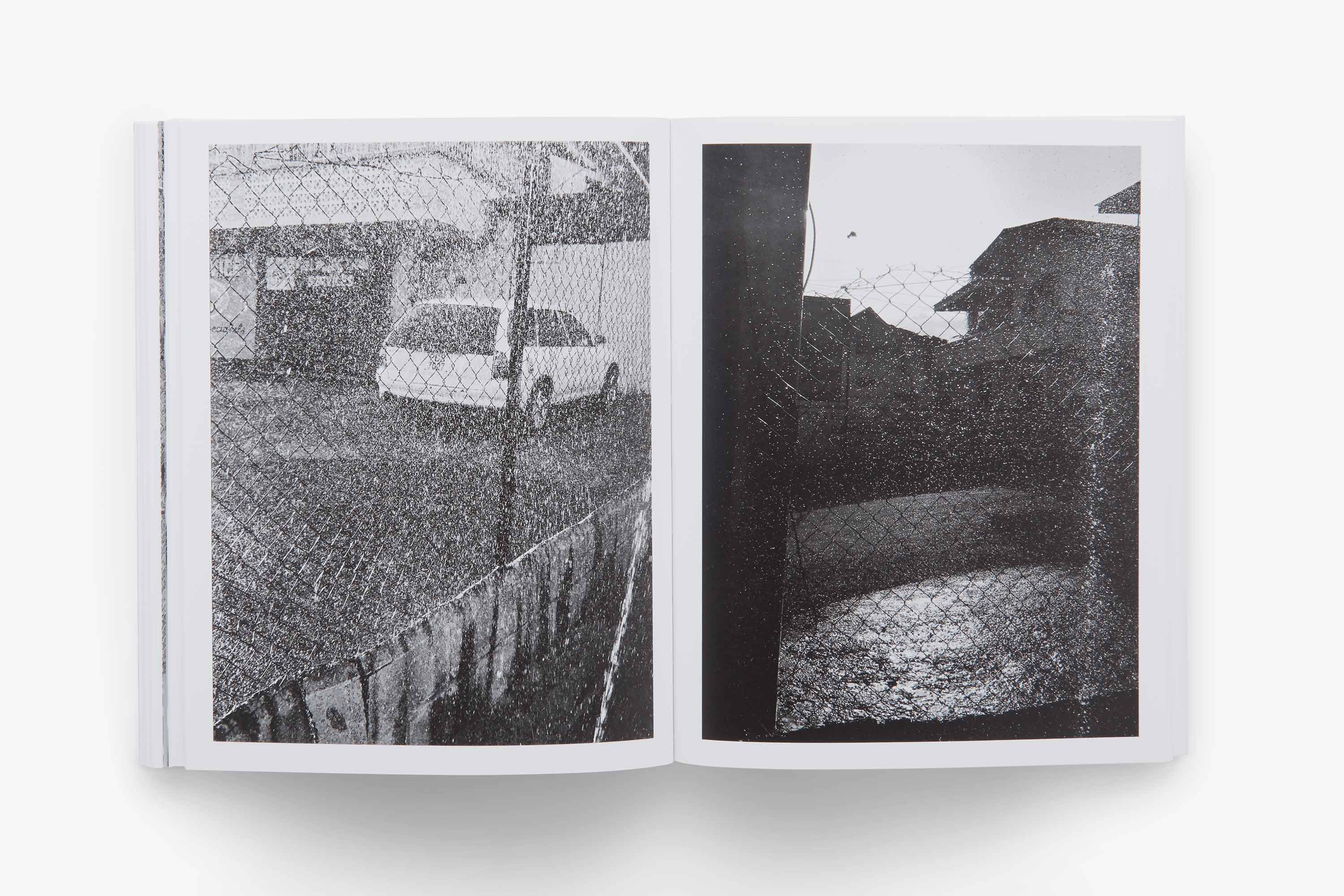

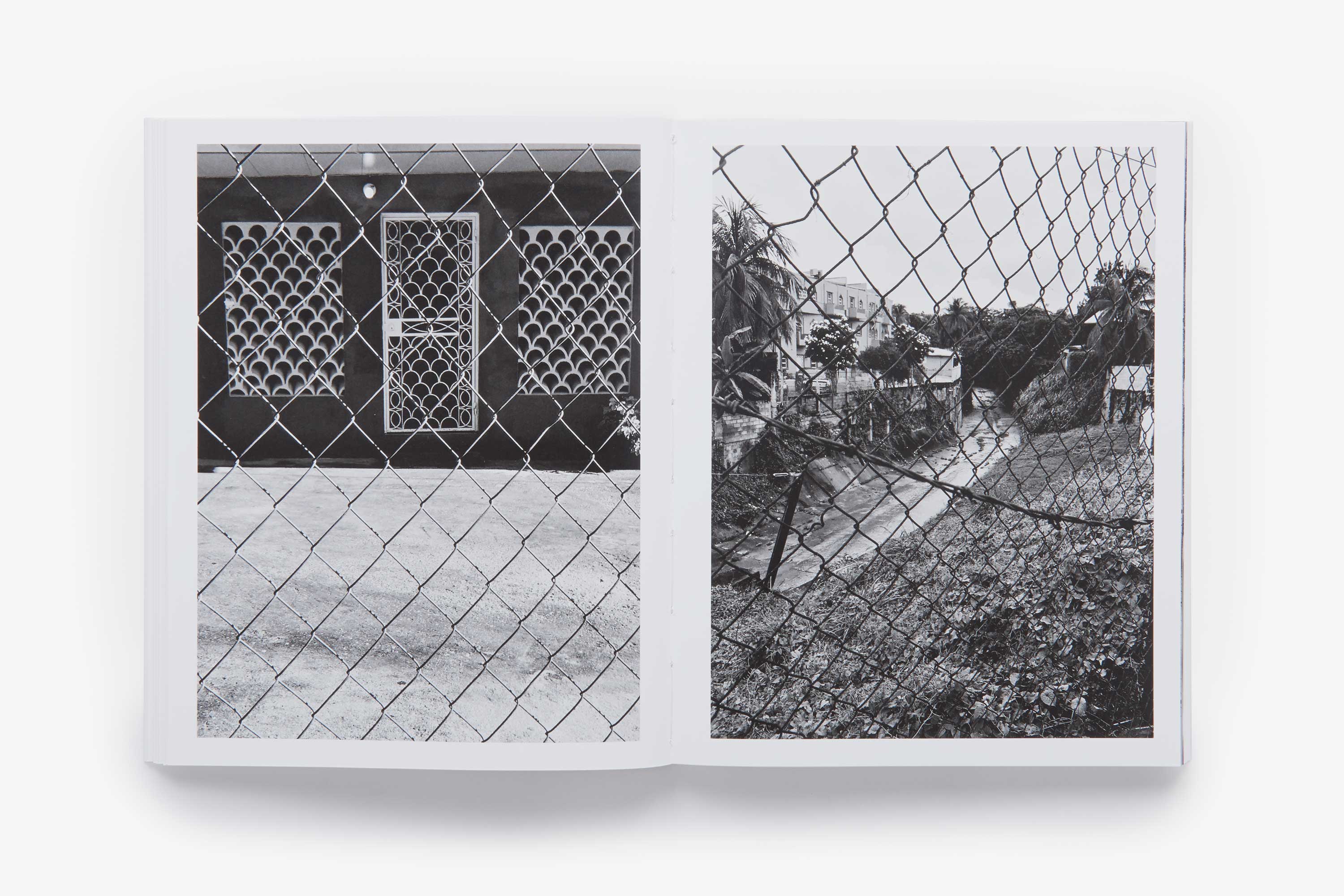

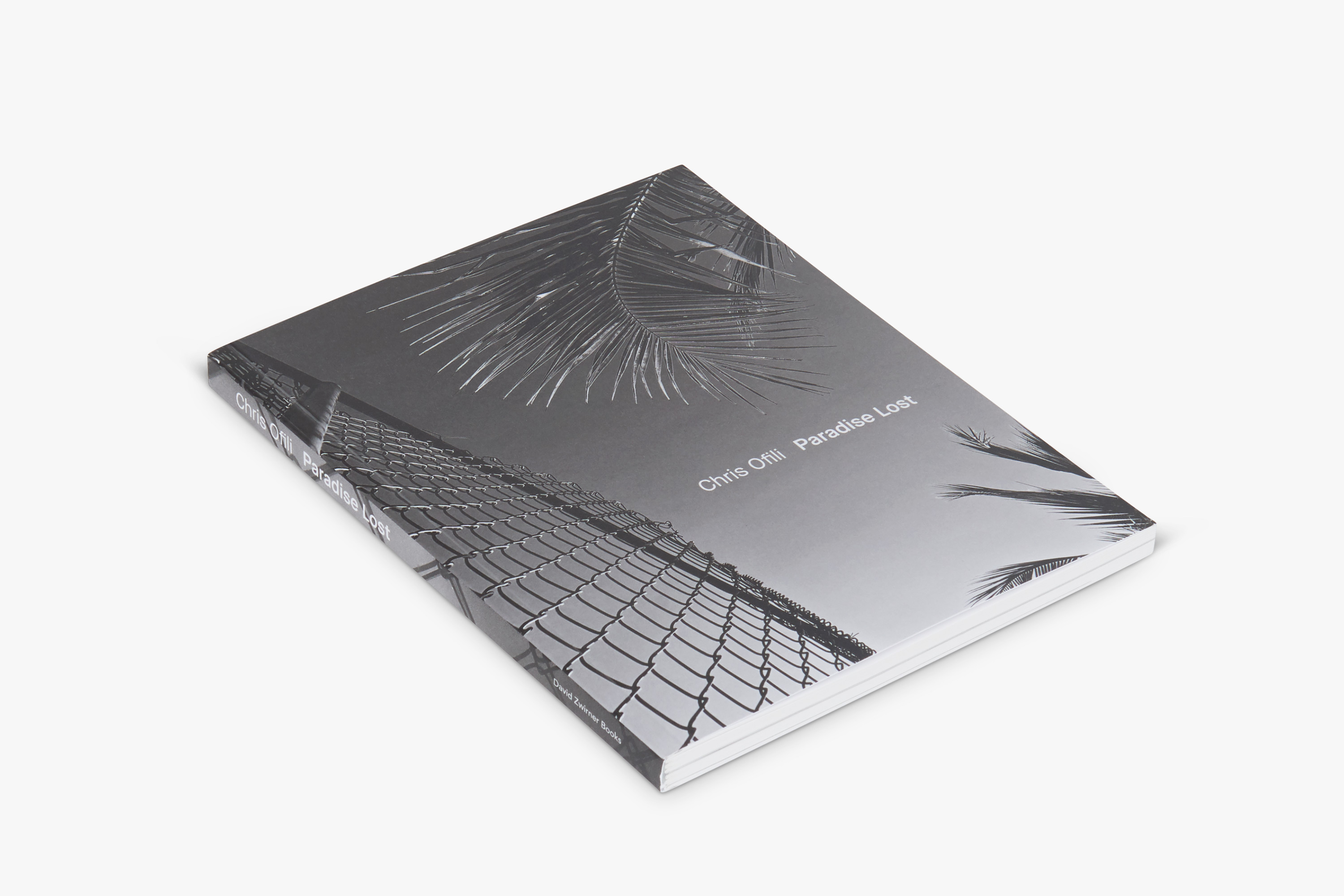

In 2017, Chris Ofili photographed chain-link fences throughout the island of Trinidad in order to explore notions of beauty, community, liberation, and constraint. This series of arresting images—“pocket photography,” as described by the artist—is the first body of photography ever published by Ofili. Through these entrancing black-and-white photographs, the artist engages with the diverse sources that inspired his critically acclaimed Paradise Lost exhibition at David Zwirner, New York in the fall of 2017.

Since moving to Trinidad in 2005, Ofili has continued to engage with the surrounding environment and culture, which has found its way into many of his colorful paintings. In these deceivingly simple black-and-white photographs, he captures a wide cross section of Trinidad as he highlights the encounter between natural and man-made settings, and the different aesthetic possibilities each brings out in the other. In focusing on a ubiquitous and seemingly unremarkable piece of equipment, Ofili is able to comment on our interactions with space and each other, using a near-universal subject as the fence slices the sky, melds into a tree, frames a basketball game, or reveals an opening.

In a new essay by the critically acclaimed author of Island People: The Caribbean and the World (2016), Joshua Jelly-Schapiro charts the history of chain-link fences; focusing on a selection of Ofili’s photographs, he then begins to explore what this imagery tells us about Trinidad in particular and the Caribbean as a whole. These two essays—one visual, the other literary—open onto a whole new set of interpretive possibilities for this groundbreaking artist.