1ère édition tirée à 600 exemplaires.

1st edition of 600 copies.

« Là où la photographie se dirige en ce moment, tout le monde le devine.

En 2023, il y a ceux qui sont convaincus que la narration par imagerie ne nécessite plus un outil obsolète ou désuet comme l’appareil photo; ceux qui savent que le mot, grâce à Midjourney, BlueWillow et des centaines d’autres algorithmes, peut devenir une image; ceux qui utilisent l’intelligence artificielle ou d’autres systèmes créatifs qui excluent toute référence à la tradition ou à la coutume, et ceux qui croient qu’il est devenu inutile de voir et de regarder pour créer des images. En bref, ce que deviendra la photographie peut être dit par ceux qui seront là, en supposant que le terme « photographie » restera toujours utilisé, étant donné que la lumière ne sera plus nécessaire – comme le veut l’étymologie du terme – pour que l’« écriture » ait lieu.

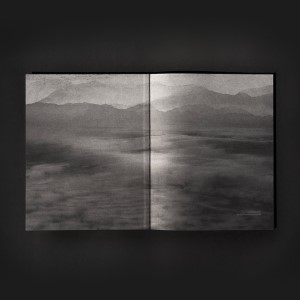

Ces questions et réflexions surgissent naturellement en regardant à travers les images prises par Stefano De Luigi lors de son long voyage à travers l’Italie, à la recherche de traces de ce qui était autrefois appelé le Bel Paese. Nous sommes confrontés à une description « véridique » des paysages italiens, et pourtant le récit classique – avec ses noirs tous aux bons endroits et aux bonnes couleurs respectés comme ils devraient l’être, auquel il nous avait habitués à travers ses projets précédents – cède ici la place à l’utilisation d’un système narratif différent, à des techniques différentes, qui suggèrent, interprètent une réalité que le Viaggio in Italia – entrepris en 1984 par Luigi Ghirri et ses compagnons de voyage – nous a déjà enseigné à voir. La question posée par De Luigi n’est pas différente de celle que Luigi Ghirri, Gianni Leone et Enzo Velati ont posée à leurs propres amis photographes, puis les créateurs inconnus du projet de révision de la transcription du territoire qui donnerait lieu à une « école italienne du paysage » : qu’est-ce qu’un Grand Tour pourrait nous apprendre de l’Italie d’aujourd’hui ? Mais les trois conservateurs des années 1980s ont largement parcouru les archives de ceux qui s’étaient consacrés à l’exploration du territoire, en partant de la conscience que la façon de « regarder et de voir » avait changé, et que le Bel Paese ne l’était plus. Stefano De Luigi, quant à lui, a pris plusieurs fois des avions, des trains et des voitures pour parcourir les 4365 kilomètres du périmètre italien, couvrant près de 20000 kilomètres au total. A différentes étapes, rentrer chez lui, repenser, imprimer des planches contacts sur lesquelles réfléchir et corriger les épreuves qui pourtant maintiennent intactes la poésie de sa vision, de cette autre vision, conçu peut-être comme un moyen de redonner sa dignité à des lieux qui n’ont pas toujours su la préserver eux-mêmes.

Mais commençons par le début. De Luigi rappelle que son amour pour la narration du paysage est né du souvenir des visites au Museo di Roma, Palazzo Braschi, qui ont animé les dimanches de son enfance. Les peintures fascinantes des vedutisti des dix-huitième et dix-neuvième siècles parlaient d’un pays magique, une sorte de jardin de délices que les jeunes riches de toute l’Europe devaient visiter. Et que le jeune De Luigi, grâce à l’imposition de son père, a commencé à détester. Le temps, la mémoire et la distance le conduiraient cependant à relire les souvenirs autrement, à rouvrir des questions restées sans réponse.

L’idée du voyage, cependant, lui plaisait. Il en avait déjà entrepris un dans le monde entier, de quatre ans à partir de 2003, pour documenter les différentes réalités des aveugles dans seize pays, à travers quatre continents différents. En 2017, armé de téléphones portables, il retrace les voyages d’Ulysse en Mediterranée. C’est peut-être avec cette expérience qu’il a commencé une réflexion sur la façon d’aborder la photographie sans appareil photo.

Et nous voici arrivés à ses voyages en Italie, qui n’est plus son pays de résidence, et qu’il pourrait commencer à revisiter, peut-être, à partir de ses propres souvenirs. Il a exprimé ses intentions dès le début : « Le projet vise à donner une image différente de l’Italie, latente et reflétant celle commune et classique. Interpréter le paysage contemporain de la péninsule, le long des lignes de l’image créée par les vedutisti. Je sens que j’ai trouvé la technique, dont la photographie est le langage, pour raconter ma vision après tant d’années de ce lien personnel profond, qui me lie à la mémoire des gens et des lieux, à la fois expérimentés et imaginés. Un besoin, les raisons dont je suis conscient, qui est maintenant devenu une urgence. »

Il organisa ainsi sa propre réévaluation, une sorte de longue et minutieuse vérification des changements, des destructions et des vestiges, une sorte de constatation presque primaire de l’état du territoire italien, dans lequel la beauté et la laideur sont devenues deux noms inséparables. Il étudie les vedutisti historiques, s’attaque aux stéréotypes qui enchantent les voyageurs et les touristes depuis des siècles, interroge les lieux communs et construit un long itinéraire qui suit le littoral, mais avec des digressions vers diverses grandes villes. Il se mesure aussi à l’œuvre de ceux qui, depuis la première moitié du XIXe siècle, se sont aventurés dans la photographie de voyage et ont ainsi poursuivi la tradition d’un Bel Paese imaginaire où histoire, architecture, culture, La nature et la beauté sont toutes intégrées dans one.

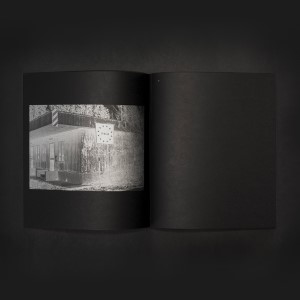

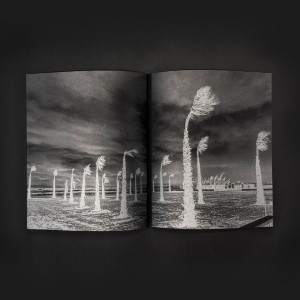

Il a divisé son itinéraire en quatre étapes : de Trieste à Ancône, Ancône à Metaponto, Metaponto à Rome et Rome à Vintimille. Neuf mois de travail. Pratiquement une gestation. Il a décidé d’utiliser une technique narrative qui, dans une certaine mesure, ramène également l’acte de la photographie à ses origines, ce qui tend à recréer le dévoilement d’une image latente. Il choisit d’inverser ses images, c’est-à-dire de passer du positif au négatif, de travailler en postproduction et de s’arrêter à un point intermédiaire, où les deux extrêmes se rencontrent et s’éloignent. Dans les vignettes qu’il a imprimées par centaines pour vérifier le progrès de son travail, les noirs et les blancs sont inversés, mais la sagesse narrative capture un moment où tout est parfaitement traçable à une image, sinon positive puis non négative, mais certainement accomplie. Cette « technique » transforme la vue en argent tout en respectant l’architecture, les arbres, la mer, les ruines, le ciel, les panneaux d’affichage, et elle empêche la dénonciation – qui, parfois, voudrait être là – de devenir telle. Est-ce une sorte de stratégie pour redonner sa dignité à un paysage qui souffre? La réponse est ouverte. De Luigi avait déjà expérimenté cette technique de réinterprétation du paysage lors d’une résidence d’artiste à Deauville, à la découverte de la Normandie des impressionnistes.

Il a lui-même défini son projet comme suit : « Alors que le terme « impressionnisme » dérive de la définition performative du peintre qui traduit ses impressions d’un paysage, d’un événement social ou des traits d’une personne, grâce à un geste rapide et des touches de couleur qui définissent l’atmosphère intime de ce qu’il a vécu, le sens de ma recherche photographique vise à définir visuellement le moment même où la lumière réfléchie imprime l’image de la scène au contact de la lumière. .matière sensible. » De Luigi voulait ainsi raconter les lieux chers aux impressionnistes en utilisant ce langage documentaire, respectueux de la réalité, cette « caresse du monde » que Walker Evans déployait il y a près de cent ans, mais en utilisant un système narratif qui, dans une certaine mesure, a ramené le moment de la perception, du plan, à sa dimension primordiale. À ce stade, l’expérience française devient une méthode, un langage, une technique, le support qui lui permet d’analyser ce qui reste de la beauté du Bel Paese, mais aussi de souligner les flux de ciment, les constructions non autorisées, l’état d’abandon, la négligence qui, grâce à l’argent de ses images, ne sert pas de condamnation mais de poésie peinée ». -Giovanna Calvenzi ; textes de Giovanna Calvenzi et Chiara Ruberti.

“Where photography is heading at the moment is anyone’s guess.

In 2023, there are those who are convinced that narration via imagery no longer requires an obsolete or obsolescent tool such as the camera; those aware that the word, thanks to Midjourney, BlueWillow and hundreds of other algorithms, can become an image; those who use artificial intelligence or other creative systems that exclude any reference to tradition or custom, and those who believe it has become unnecessary to see and look in order to create images. In short, what photography will become may be told by those who will be there, assuming that the term ‘photography’ will still remain in use, given that light will no longer be necessary – as the etymology of the term would have it – for the ‘writing’ to take place.

These questions and reflections arise naturally when looking through the images taken by Stefano De Luigi on his long journey through Italy, in search of traces of what was once called the Bel Paese. We are faced with a ‘truthful’ description of Italian landscapes, and yet the classical narrative – with his blacks all in the right places and colours respected just as they ought to be, to which he had accustomed us through his previous projects – gives way here to the use of a different narrative system, to different techniques, which suggest, interpret a reality that the Viaggio in Italia – undertaken in 1984 by Luigi Ghirri and his travelling companions – already taught us to see. The question posed by De Luigi is no different from the one that Luigi Ghirri, Gianni Leone and Enzo Velati posed to their own photographer friends, then the unknowing creators of the project to revise the transcription of the territory that would give rise to an ‘Italian school of landscape’: what might a Grand Tour tell us about today’s Italy? But the three curators in the 1980s travelled largely through the archives of those who had dedicated themselves to investigating the territory, starting from the awareness that the way of ‘looking and seeing’ had changed, and that the Bel Paese was no longer such. Stefano De Luigi, on the other hand, took planes, trains and cars to travel the 4,365-kilometre length of the Italian perimeter several times, covering almost 20,000 kilometres in total. In various stages, returning home, rethinking, printing thumbnails on which to reflect and correct, contact prints that nevertheless maintain the poetry of his vision intact, of this other vision, conceived perhaps as a method to restore dignity to places that have not always been able to preserve it themselves.

But let us start at the beginning. De Luigi recalls his love for narrating the landscape was born from the memory of visits to the Museo di Roma, Palazzo Braschi, which animated the Sundays of his childhood. The fascinating paintings of the vedutisti of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries told of a magical country, a sort of garden of delights that wealthy young people from all over Europe had to visit. And which the young De Luigi, thanks to his father’s imposing of it, instead began to detest. Time, memory and distance would however lead him to reread memories differently, to reopen questions that remained unanswered.

The idea of the journey, however, was congenial to him. He had already undertaken one around the world, of four years starting in 2003, to document the different realities of the blind in sixteen countries, across four different continents. In 2017, armed with mobile phones, he retraced Ulysses’ travels across the Mediterranean. Perhaps it was with this experience that he began a reflection on how to approach photography without a camera.

And here we come to his travels in Italy, which is now no longer his country of residence, and which he may begin to revisit, perhaps, starting from his own memories. He stated his intentions from the outset: “The intention of the project is to deliver a different image of Italy, latent and mirroring the common and classical one. Interpreting the contemporary landscape of the peninsula, along the lines of the image created by the vedutisti. I feel I have found the technique, of which photography is the language, to tell my vision after so many years of this deep personal bond, which binds me to the memory of people and places, both experienced and imagined. A need, the reasons for which I am aware of, which has now become an urgency.”

He thus organised his own reappraisal, a sort of long, painstaking verification of the changes, destructions and remains, a sort of almost primal ascertainment of the state of the Italian territory, in which beauty and ugliness have become two inseparable nouns. He studied the historical vedutisti, tackling the stereotypes that have enchanted travellers and tourists for centuries, interrogating commonplaces and constructing a long itinerary that follows the coastline, yet with digressions towards various major cities. He also measures himself against the work of those who, since the first half of the nineteenth century, have ventured into travel photography and have thus continued the tradition of an imaginary Bel Paese where history, architecture, culture, nature and beauty are all rolled into one.

He split his itinerary into four stages: from Trieste to Ancona, Ancona to Metaponto, Metaponto to Rome and Rome to Ventimiglia. Nine months of work. Virtually a gestation. He decided to use a narrative technique that to some extent also leads the act of photography back to its origins, something that tends towards recreating the unveiling of a latent image. He chooses to invert his images, i.e. to switch from positive to negative, work in postproduction and come to a halt at an intermediate point, where the two extremes meet and move apart. In the thumbnails he printed by the hundreds to check the progress of his work, blacks and whites are inverted, but the narrative wisdom captures a moment in which everything is perfectly traceable to an image, if not positive then not negative, but certainly accomplished. This ‘technique’ turns the view to silver while respecting the architecture, the trees, the sea, the ruins, the skies, the billboards, and it prevents the denunciation – which at times would like to be there – from becoming such. Is this a sort of strategy to restore dignity to a suffering landscape? The answer is open. De Luigi had already experimented with this technique of reinterpreting the landscape during an artist residency in Deauville, discovering the Normandy of the Impressionists. He himself defined his project as follows: “While the term ‘Impressionism’ derives from the performative definition of the painter who translates his impressions of a landscape, a social event or the features of a person, thanks to a rapid gesture and touches of colour that define the intimate atmosphere of what he has experienced, the sense of my photographic research sets out to visually define the very moment in which the reflected light imprints the image of the scene in contact with light-sensitive material.” De Luigi thus aimed to narrate the places dear to the Impressionists using that documentary language, respectful of reality, that “caressing of the world” which Walker Evans deployed almost a hundred years ago, but using a narrative system that to some extent took the moment of perception, of the shot, back to its primordial dimension. At this point, the French experience becomes a method, a language, a technique, the medium that allows him to analyse what is left of the beauty of the Bel Paese,but also to point out the cement flows, the unauthorised constructions, the state of abandonment, the sloppiness, which thanks to the silver of his images, do not serve as condemnation but as pained poetry.” -Giovanna Calvenzi ; texts by Giovanna Calvenzi and Chiara Ruberti.