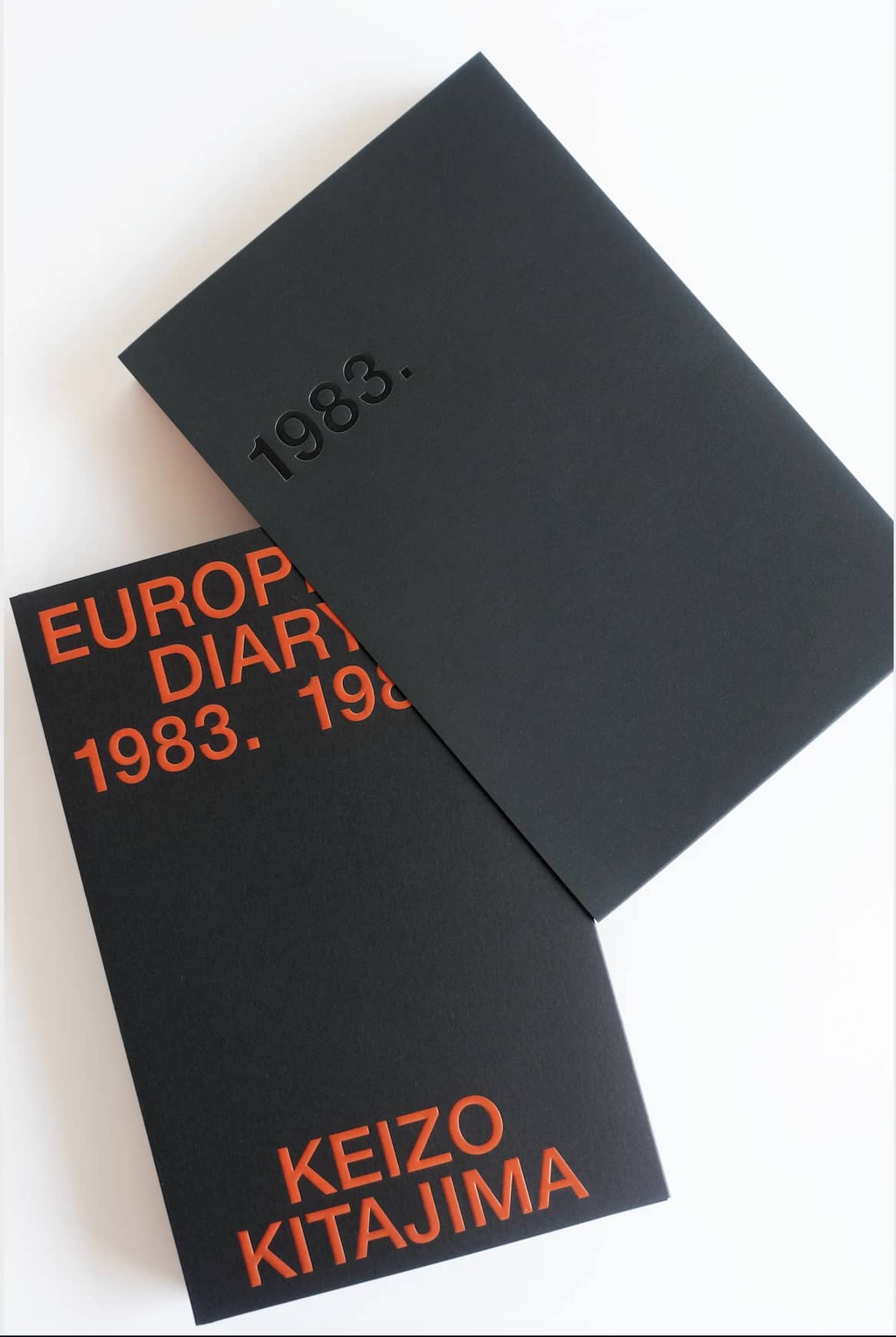

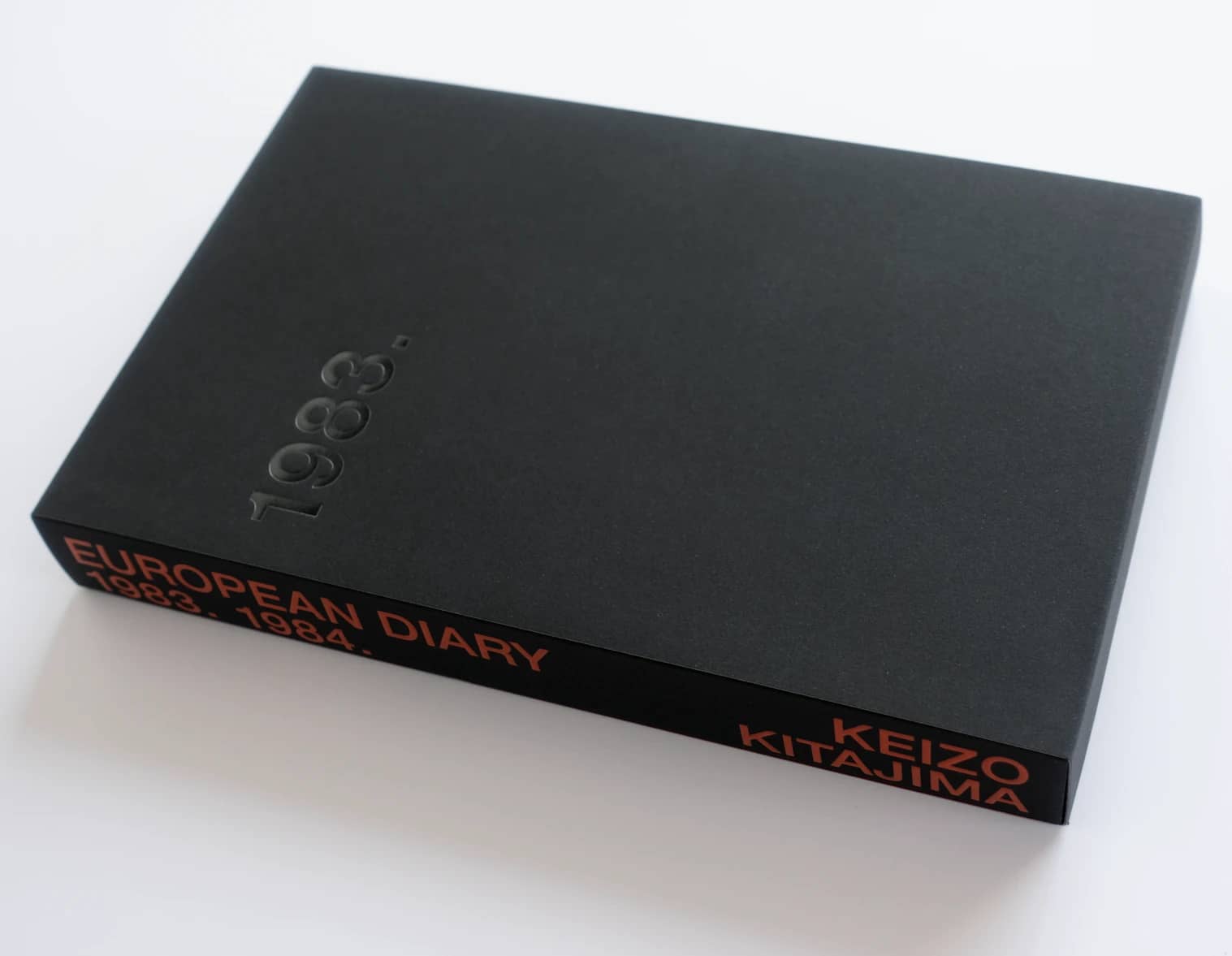

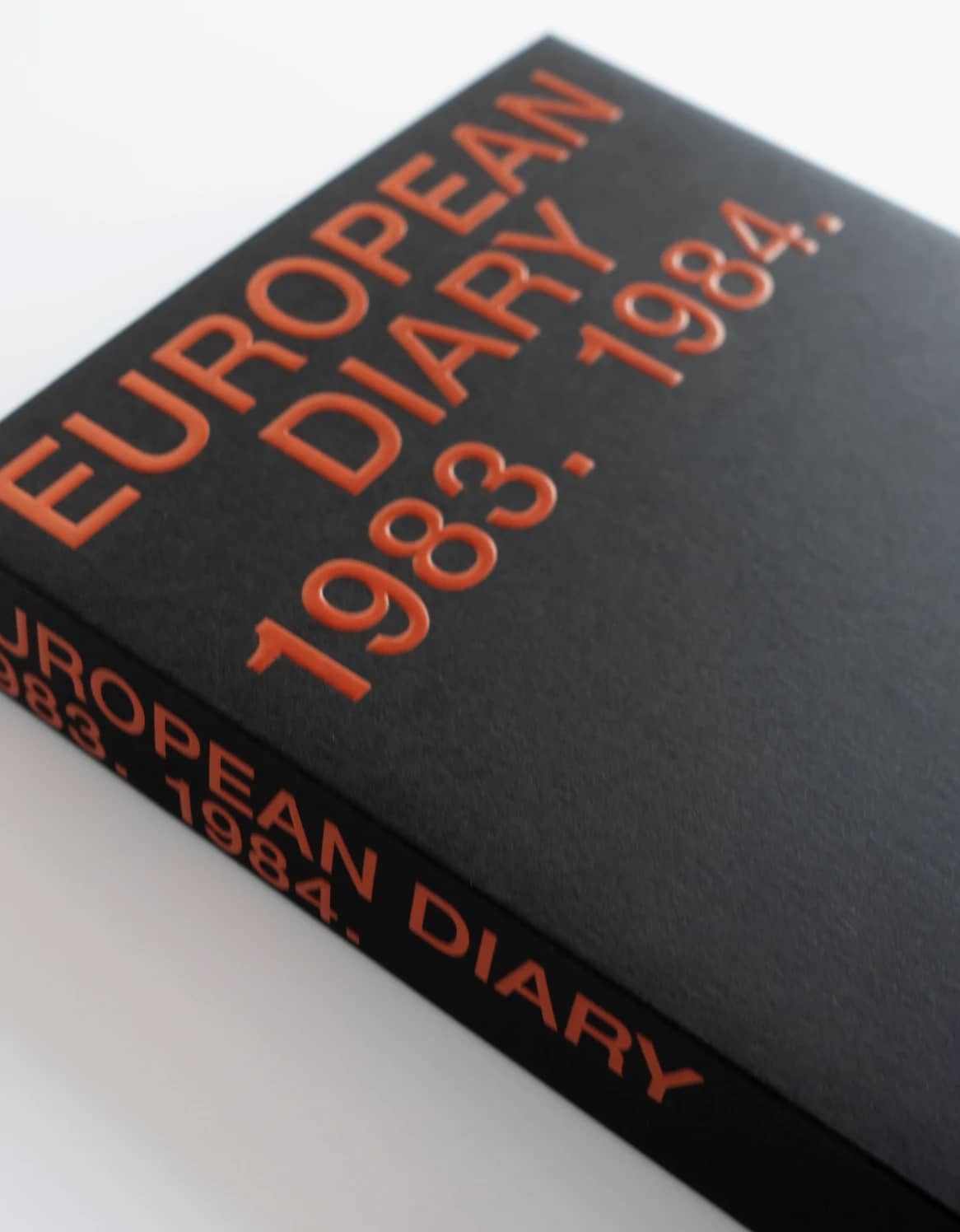

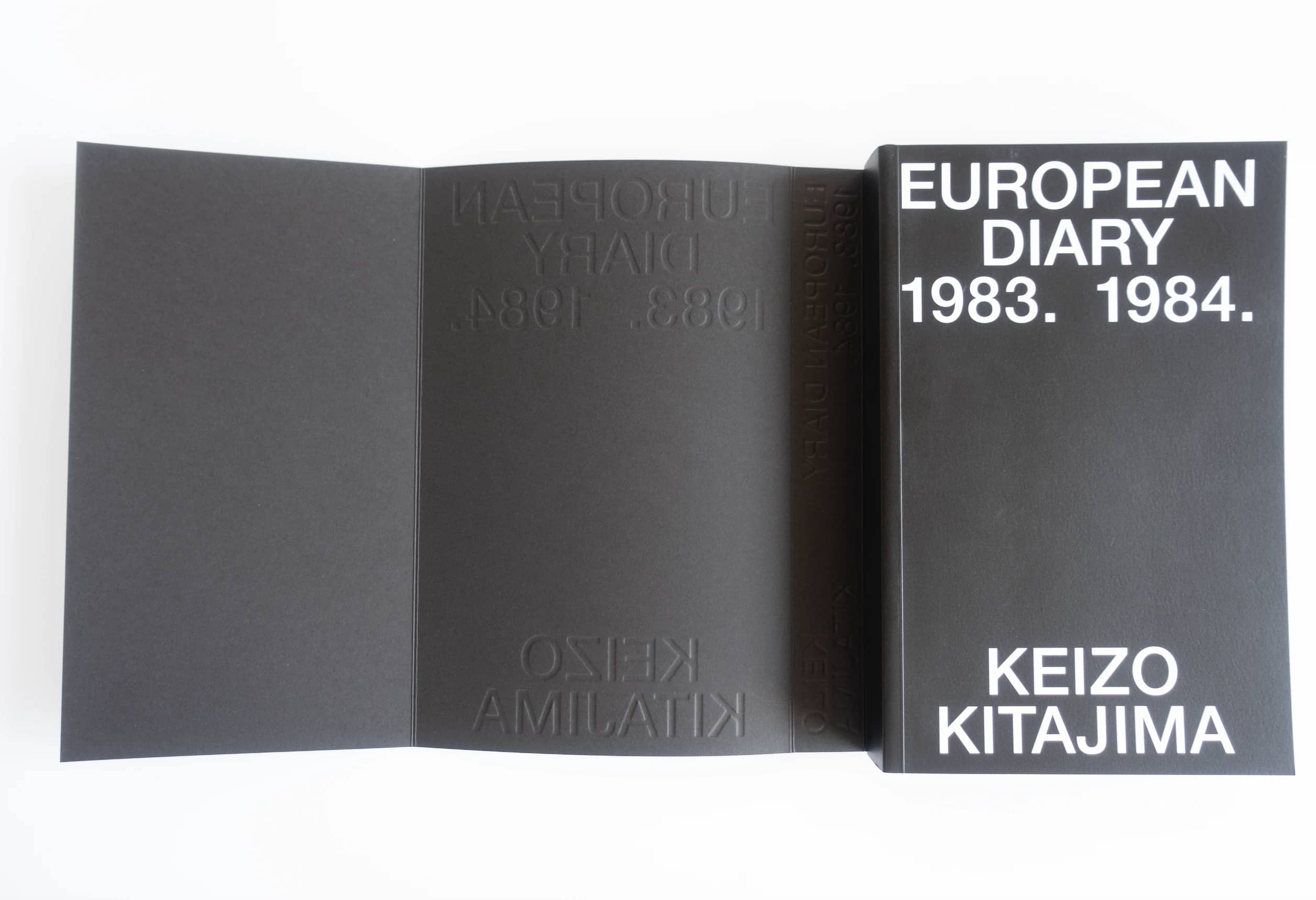

1ère édition tirée à 500 exemplaires.

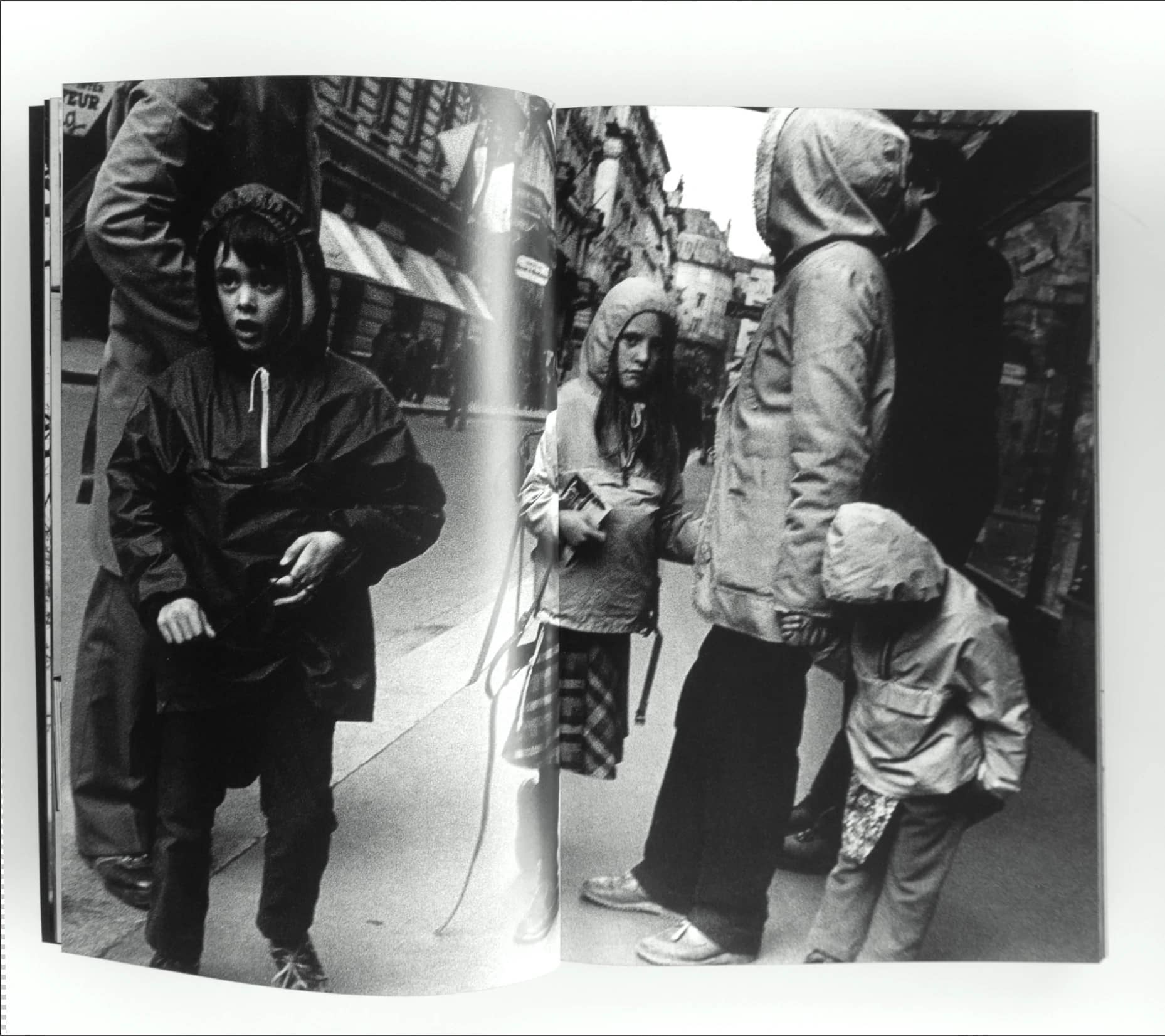

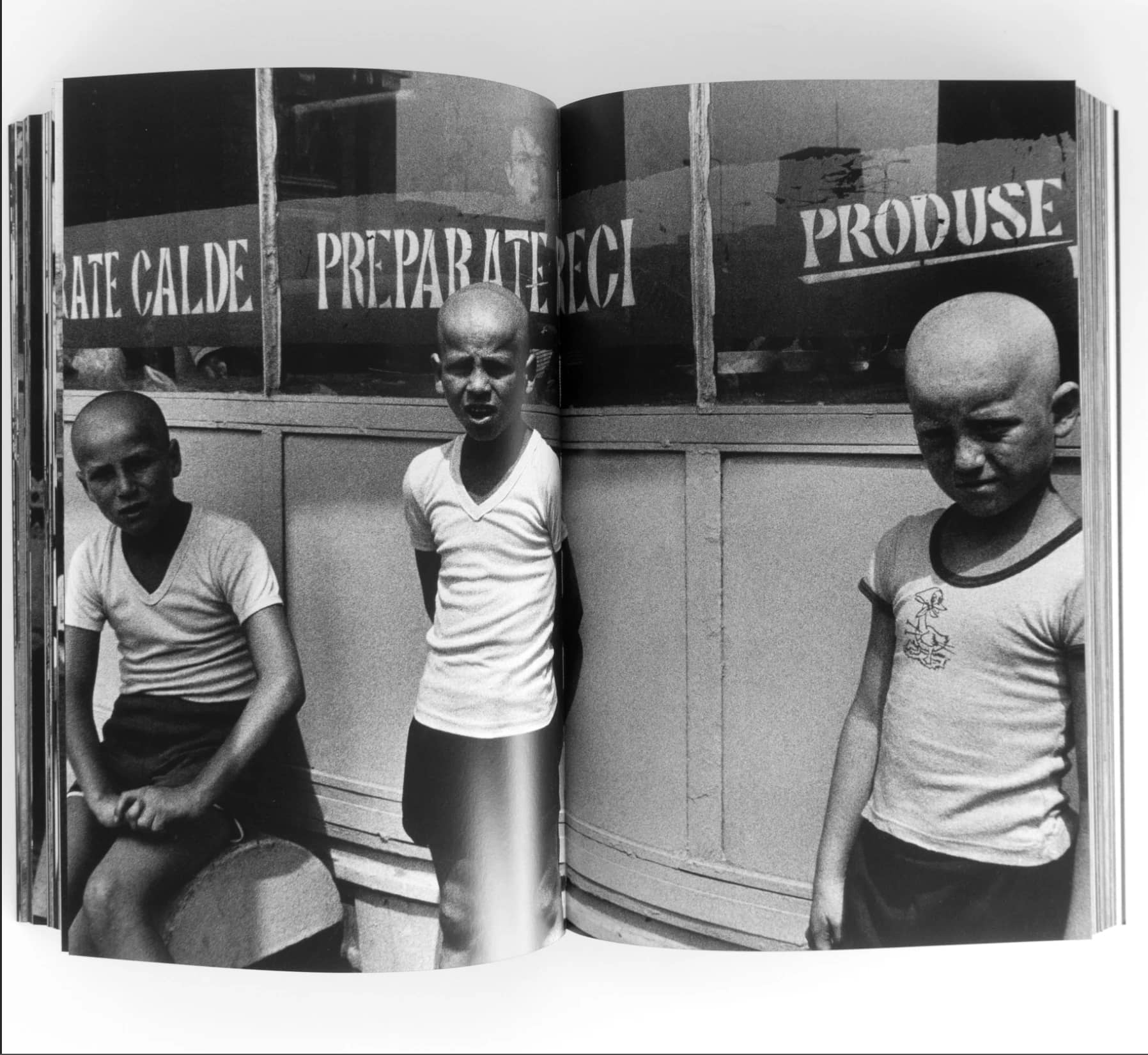

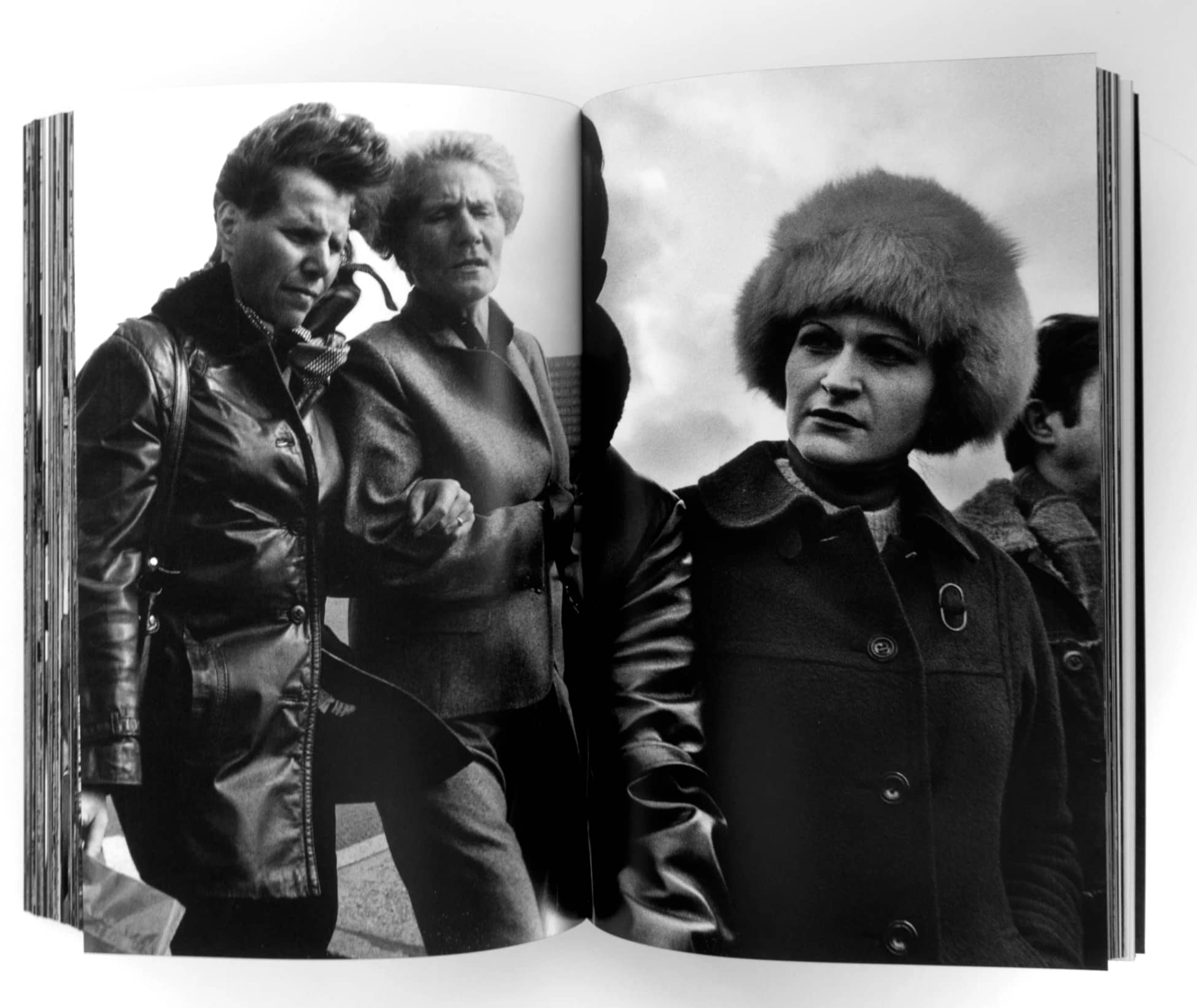

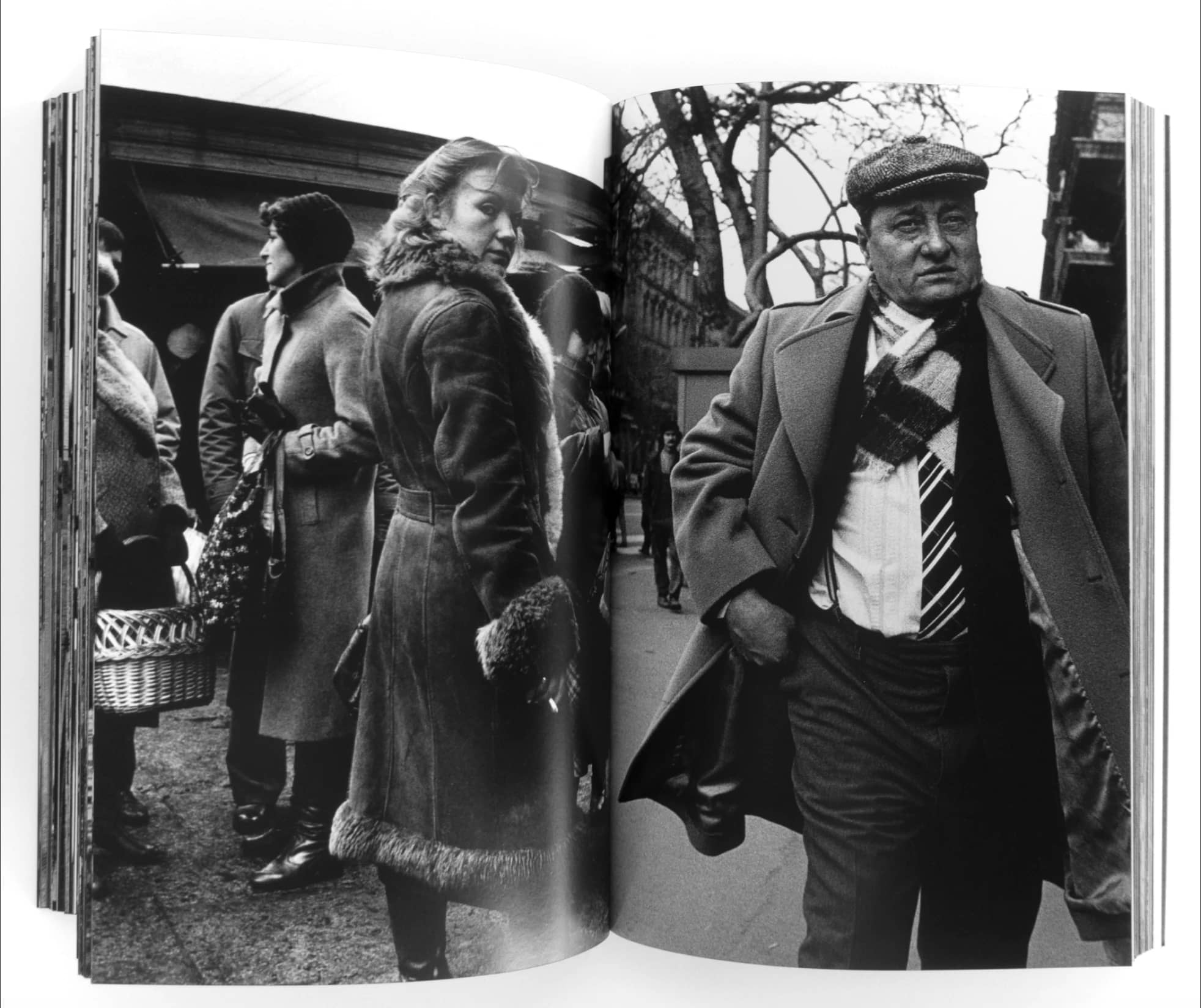

Sauf pour certainEs, presque toutes les photographies n’ont pas été publiées ou exposées publiquement avant cette publication. Il n’est pas rare que les images restent longtemps invisibles car d’innombrables photos sont souvent conservées dans nos appareils numériques sans jamais être vues à nouveau. Keizo Kitajima s’est rendu en Europe de l’Est en 1983 pour prendre ces photos en tant que photographe et non en tant que touriste, mais pour que celles-ci soient restées invisibles malgré son intention initiale de les exposer, implique une opération spécifique et étrange qui porte directement sur la question « Quand devient-on photographe ? » Cette publication, en effet, apporte une réponse : ce n’est qu’après 35 ans que Kitajima est devenu photographe de ces sites.

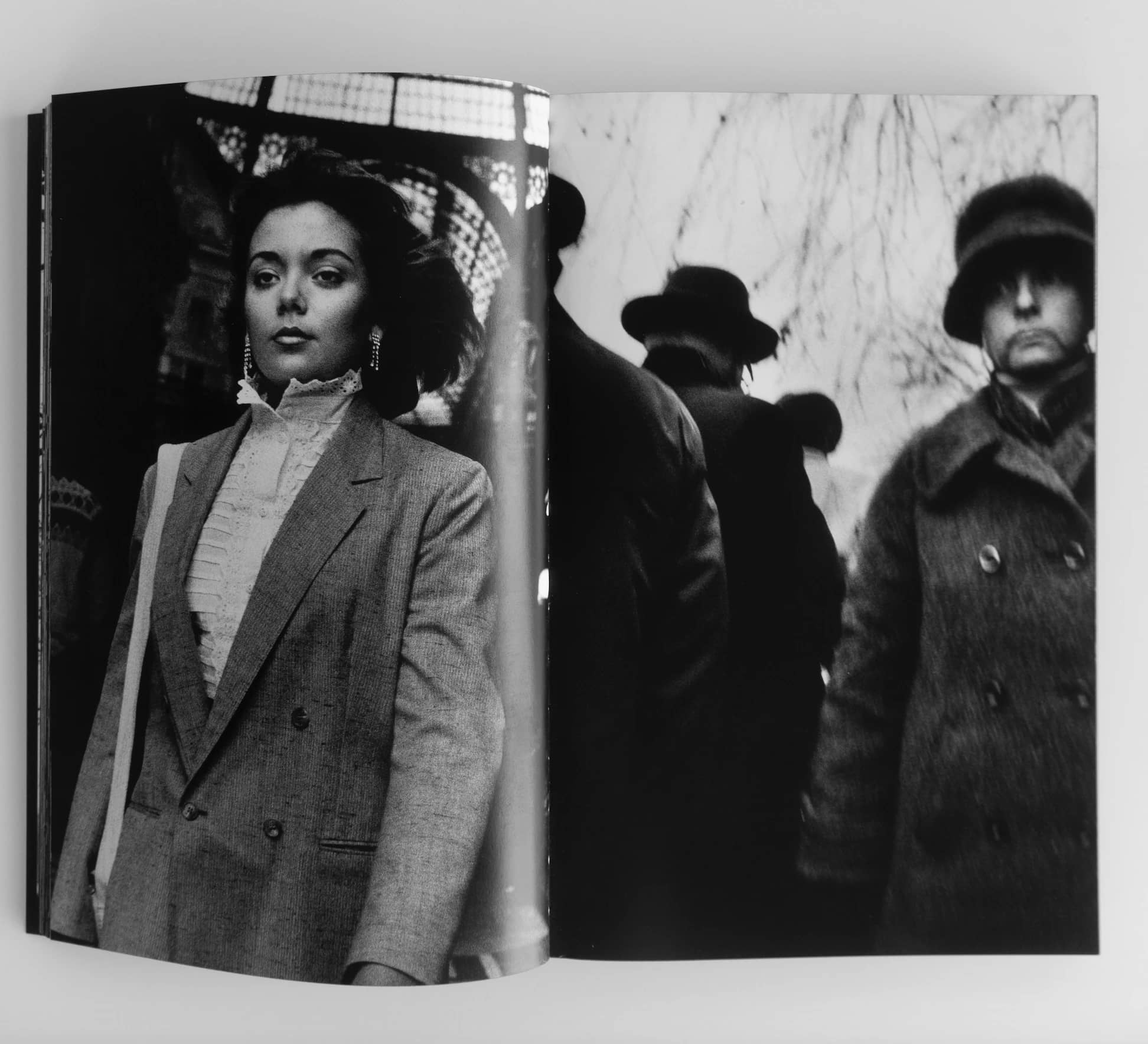

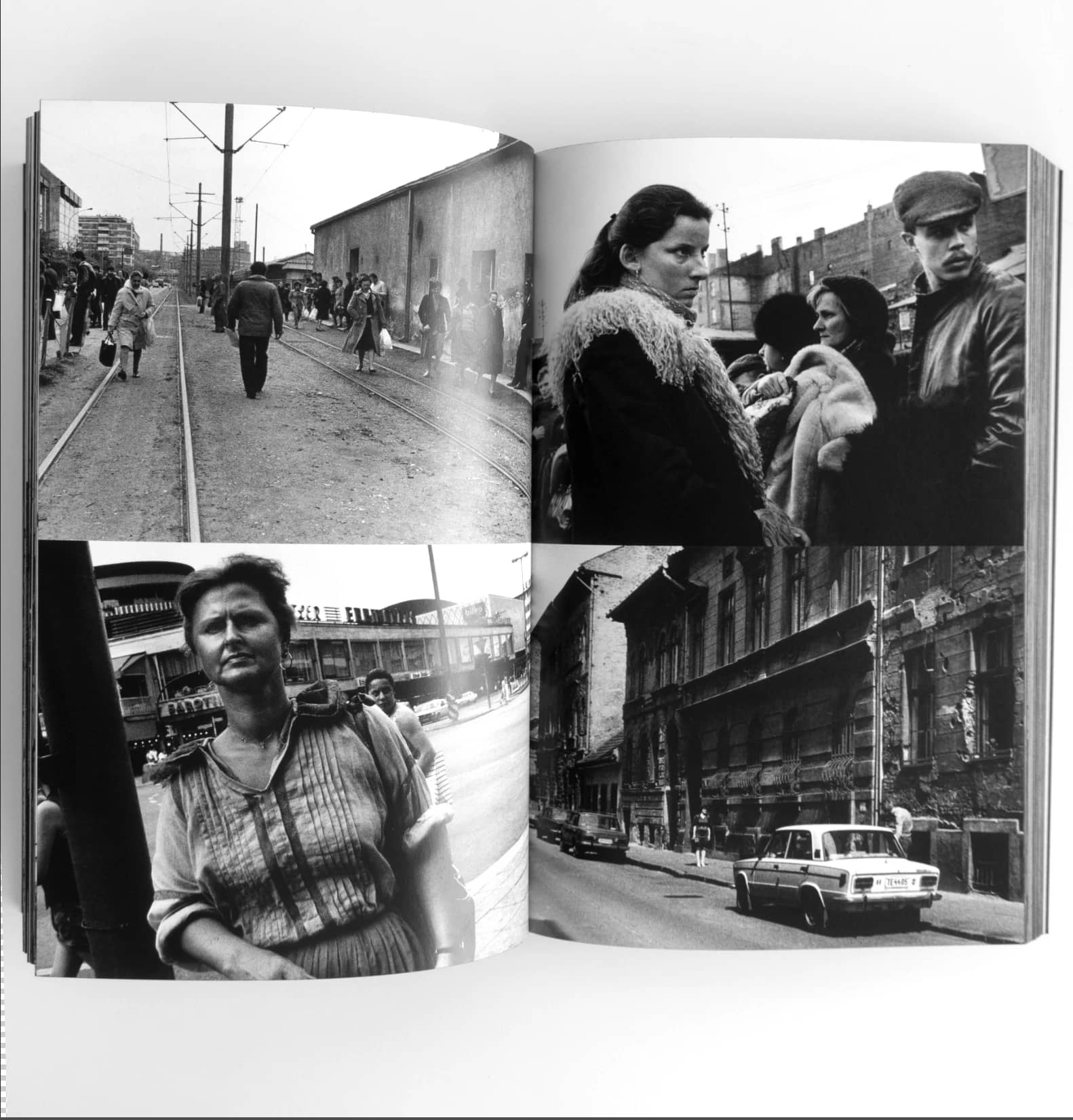

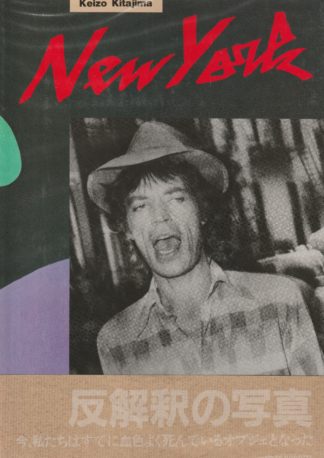

En d’autres termes, il a fallu environ 30 ans pour que ces photographies deviennent publiables. L’écart des années génère la distance absente quand il a pris les photos. Ces images sont tout aussi distantes pour lui maintenant qu’elles le sont pour nous. Il était physiquement présent à Berlin, Varsovie et Prague lorsqu’il a pris ces photos de 1983 à 1984. Cette distance dans le temps empêche quiconque de posséder ces vues comme les siennes, y compris Kitajima. Le photographe qui pourrait prétendre que ces photos ont été prises hier ne peut pas exister en raison du temps qui s’est écoulé. Kitajima a passé 35 ans à démêler cet écart entre le regard mécanique et le regard personnel. Nous devrions considérer sa carrière comme une lutte constante contre cet écart. Ses premières activités, y compris le magazine « Photo Express Tokyo », où il publiait des instantanés au flash pour augmenter le contraste, visaient à éloigner les téléspectateurs dont l’accent mis sur « avoir vu » et « être là » masquait le regard mécanique. Ce vol couvre ses voyages à Okinawa et à New York, ainsi que ceux qu’il a pris en Europe de l’Est et en Union soviétique au bord de l’effondrement.

A strictly limited edition of 500 copies.

Save for some, nearly all the photographs here have not been published or publicly exhibited prior to this publication. It is not rare for pictures to remain unnoticed for a long time because innumerable photos are often kept in our digital devices without ever being seen again. Keizo Kitajima travelled to Eastern Europe in 1983 to take these pictures as a photographer and not as a tourist, yet for these to have remained unseen despite his initial intention to exhibit them, involves a specific if strange operation which bears directly on the question » when does one become a photographer? » This publication, in fact, provides an answer: only after 35 years did Kitajima become a photographer of these sites.

In other words, 30 years or so were necessary for these photographs to become publishable. The gap of years generates the distance absent when he took the photos. These images are just as distant to him now as they are to us. He was physically present in Berlin, Warsaw, and Prague when he took these pictures from 1983 to 1984. This distance in time prevents anyone from possessing these views as their own, including Kitajima. The photographer who might claim that these were taken just yesterday cannot possibly exist because of the amount of time that has lapsed. Kitajima spent 35 years to tease out this gap between the mechanical and personal gaze. We should read his career as a constant struggle with this gap. His early activities, including the “Photo Express Tokyo” magazine where he published snapshots using flash to increase contrast, was meant to get away from those viewers whose emphasis on the « having seen » and “being there” obscured the mechanical gaze. This flight underwrites his trips to Okinawa and New York, as well as the ones he took to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union on the verge of collapse.

Keizo Kitajima was born in 1954 in Suzaka (Nagano Prefecture), Japan. He began photography at an early age; his discovery of the precursory works of Nobuyoshi Araki and Daidō Moriyama marked his teenage years. He was an original member of the Workshop Photo School. Like Moriyama, Kitajima developed an interest in the creative potential of photography’s reproducibility, but he took the notion of transformation in a very different direction, focusing on the layers of reproduction in his own work rather than the degeneration of cultural media. Kitajima’s photography is haunted by an obsession: identity, or rather the opposite; what Kitajima himself calls un-identity.