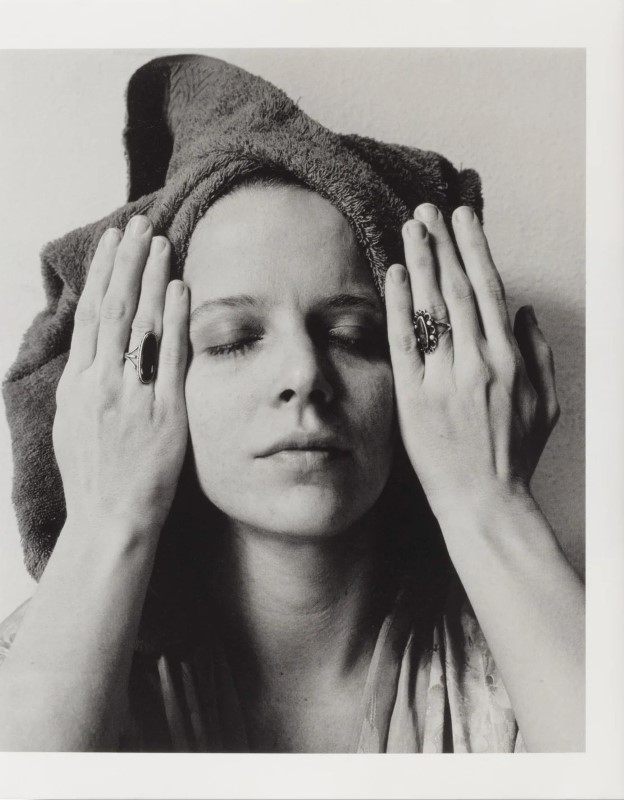

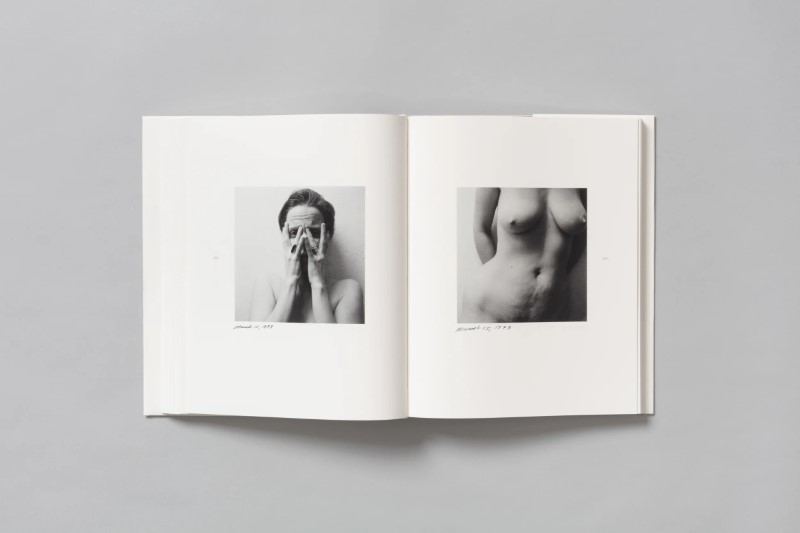

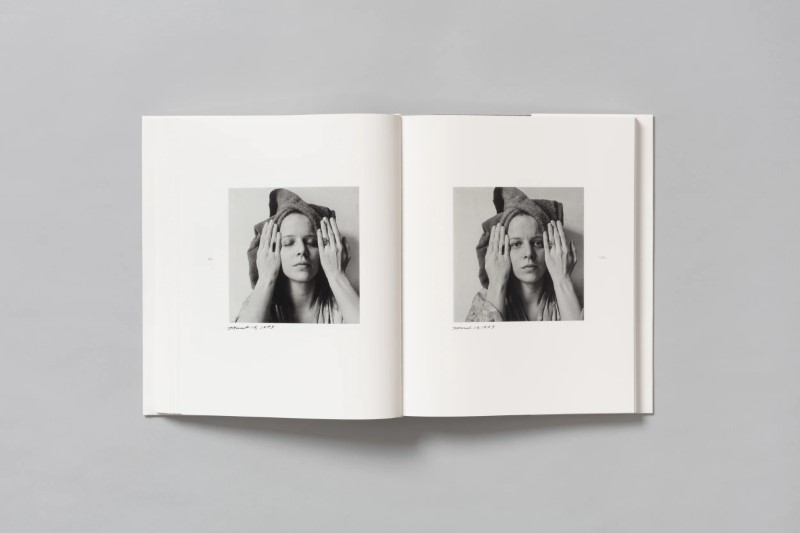

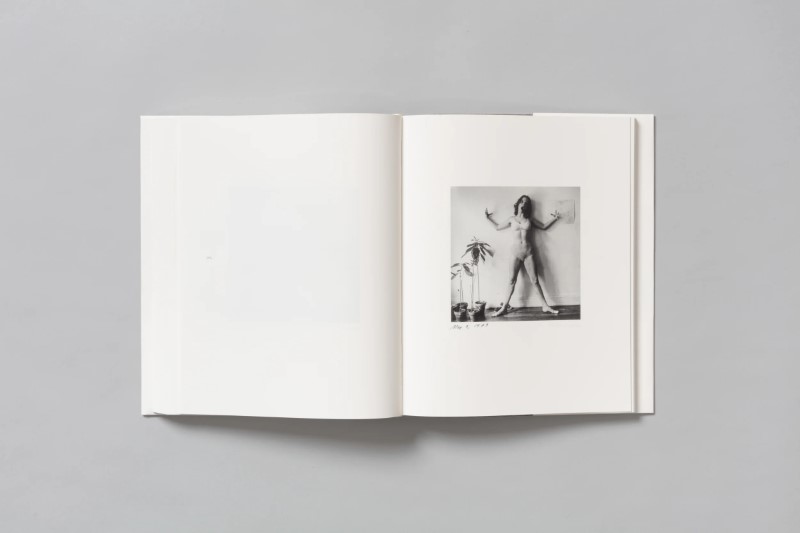

En décembre 1972, Melissa Shook (1939-2020) entreprend une série d’autoportraits quotidiens dans son appartement du Lower East Side qu’elle poursuivra jusqu’en août 1973. Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973 est la série complète de 192 photographies publiées pour la première fois par l’artiste. Avec son moyen format, ses photographies en noir et blanc, Melissa Shook se photographie dans une variété de poses, créant un portrait plus complet que celui qui pourrait être réalisé avec une seule image. Les photographies incluent souvent la fille de Melissa Shook et les amis qui peuplent sa sphère. Le spectateur est introduit au domaine intime de l’artiste et la mondanité de l’existence quotidienne vient à l’avant-plan : allaiter son orteil malade sur le canapé, s’asseoir à la table de la cuisine avec un ami, les cheveux emmitouflés dans une serviette de douche, danser avec sa fille. Plutôt que d’incarner strictement une vision typique de la beauté, les poses de Melissa Shook sont souvent imprégnées d’irrévérence et de parodie comme un rejet de la tradition du portrait féminin fait à partir d’une perspective masculine. Le livre est astucieusement contextualisé par l’essai de Sally Stein soulignant le rejet délibéré de l’artiste de l’idée d’un seul moment révélateur, optant plutôt pour le portrait en série étendu, avec toutes ses contradictions et sa complexité.

In December 1972, Melissa Shook (1939–2020) began a series of daily self-portraits in her Lower East Side apartment that she would continue until August 1973. Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973 is the artist’s complete series of 192 photographs published together for the first time. With her medium format, black and white photographs, Shook captures herself in a variety of poses creating a more complete portrait than could be achieved with any one image. The photographs often include Shook’s daughter and the friends who populate her sphere. The viewer is introduced to the artist’s intimate domain and the mundanity of everyday existence comes to the forefront: nursing her ailing toe on the couch, sitting at the kitchen table with a friend, hair wrapped up in a towel post shower, dancing with her daughter. Rather than strictly embodying a typical vision of beauty, Shook’s poses are often imbued with irreverence and parody as a rejection of the tradition of female portraiture made from a male perspective. The book is astutely contextualized by Sally Stein’s essay highlighting the artist’s purposeful dismissal of the idea of a single, revelatory moment, opting instead for the extended serial portrait, with all its contradictions and complexity.