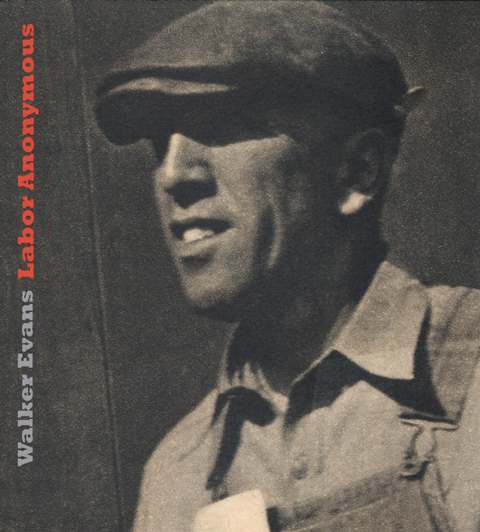

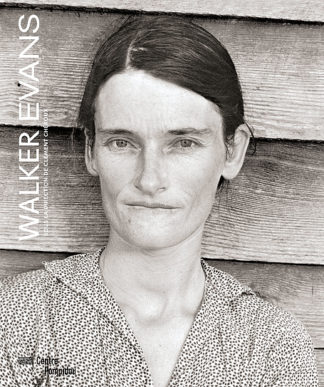

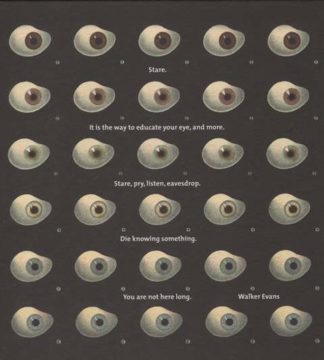

En 1938, le Museum of Modern Art de New York a consacré sa toute première exposition de photographie solo au travail d’Evans, et il a façonné l’image de l’Amérique d’elle-même, en particulier à travers ses photographies de la Grande Dépression. La publication « Walker Evans: Labor Anonymous » est la première enquête approfondie sur une série du même nom, publiée par Evans dans le magazine Fortune en 1946. Un samedi après-midi à Detroit, Evans se positionne avec sa caméra Rolleiflex sur le trottoir. et photographié des piétons, pour la plupart des ouvriers, à sa manière typiquement claire et sans ornement – une esthétique qu’il a consciemment décrite comme le «style documentaire». Comme dans sa série précédente, par ex. dans les célèbres « Portraits de métro » du métro de New York, ses sujets ignoraient souvent qu’ils étaient photographiés, mais certains des piétons regardaient aussi directement dans la caméra. Représentant bien plus qu’une simple typologie, cette série photographique n’offre pas une image fixe de l’humanité ou de la classe ; photos en n.b., textes de David Campany, Heinz Liesbrock et Jerry L. Thompson.

In 1938 the Museum of Modern Art in New York dedicated its first ever solo photography exhibition to Evans’s work, and he has shaped America’s image of itself particularly through his photographs of the Great Depression. The publication « Walker Evans: Labor Anonymous » is the first in-depth investigation into a series of the same name, which Evans published in Fortune magazine in 1946. On a Saturday afternoon in Detroit, Evans positioned himself with his Rolleiflex camera on the sidewalk and photographed pedestrians, mostly laborers, in his characteristically clear and unadorned way – an aesthetic he consciously described as the « documentary style ». As in his earlier series, e.g. in the famous « Subway Portraits » from the New York underground, his subjects were often unaware they were being photographed, but some of the pedestrians also looked straight into the camera. Representing much more than a simple typology, this photographic series does not offer a fixed image of humankind or class.