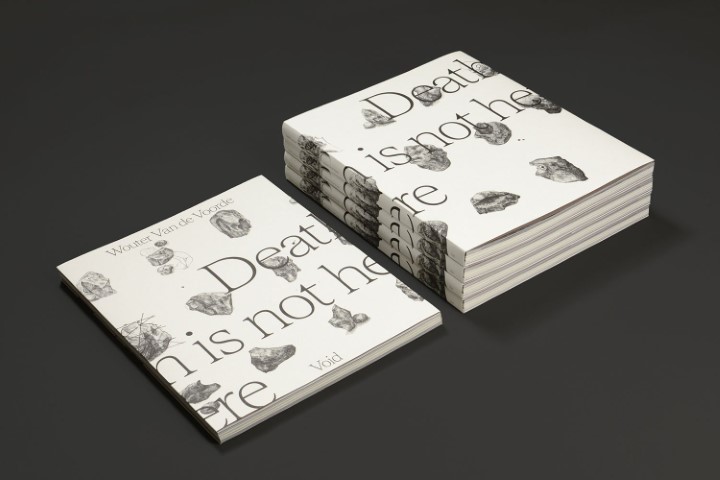

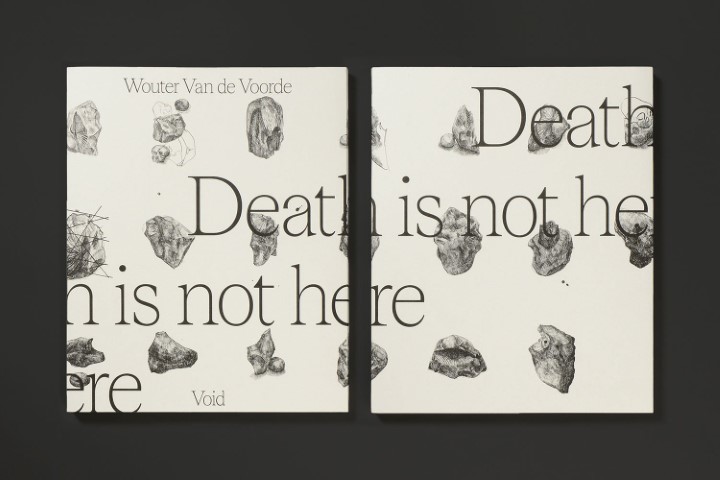

1ère édition tirée à 750 exemplaires.

1st edition of 750 copies.

Ayant étudié la peinture auparavant, Van de Voorde aborde l’éclairage et la photographie avec un œil de peintre. Les images monochromes de ce livre ont été créées sur les terres du peuple autochtone Ngunnawal, de la Première Nation et des gardiens traditionnels de la région de Canberra, en Australie.

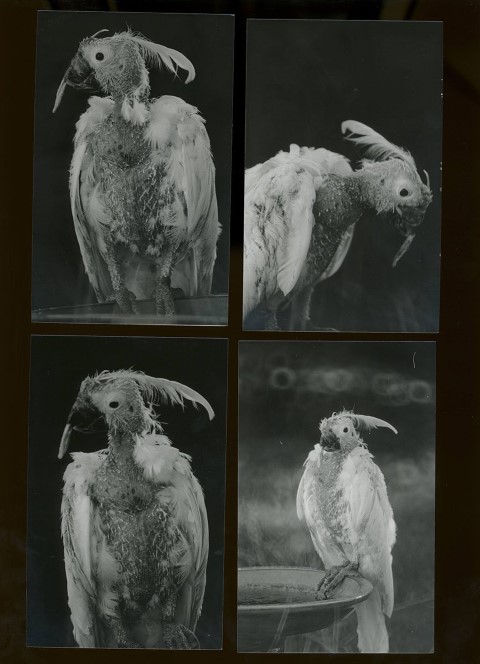

Dans le contexte de la pandémie, il était sur le point de devenir père pour la deuxième fois. Il avait fait des natures mortes avec des fossiles, et pendnat son temps libre il avait commencé à creuser dans le jardin avec son fils déterrant la tombe d’un poulet de la famille. Des photographies de fouilles ultérieures, des sculptures rocheuses, une gorge érodée et une préoccupation constante pour les corbeaux sont combinées pour créer un nouveau récit représentant les rencontres quotidiennes entre la vie et la mort.

Le livre est ponctué de photographies inquiétantes et ambiguës de trous creusés à la main. L’impulsion initiale pour créer un trou était une demande du fils de Wouter Van de Voorde de jouer dans la vraie vie à Minecraft et donc ils ont commencé à creuser dans la cour. Comme le trou devenait de plus en plus profond, Van de Voorde devint fasciné par le vide et commença à essayer de dessiner les contours des trous avec des flammes. En déterrant la tombe d’un poulet défunt, les os visibles, ils ont récolté de l’argile et utilisé pour faire feu de petits objets, comme un crâne illustré dans le livre. Les images des vides de l’arrière-cour sont entrecoupées de photographies du fils de l’artiste explorant une gorge érodée, qui ressemble à une version géante de leurs fouilles de l’arrière-cour — le père et le fils partageant des explorations de ce qui se trouve sous terre.

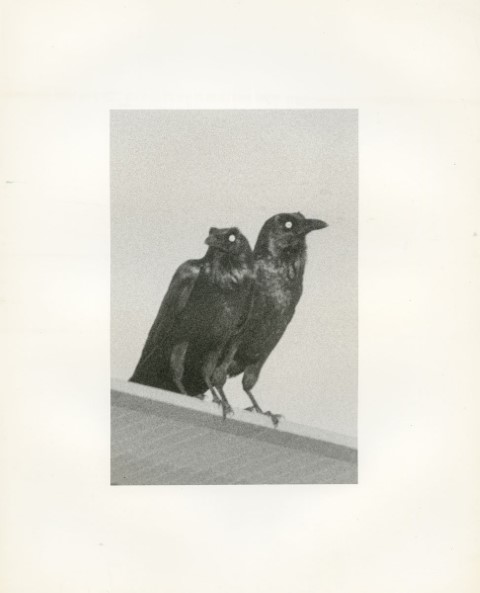

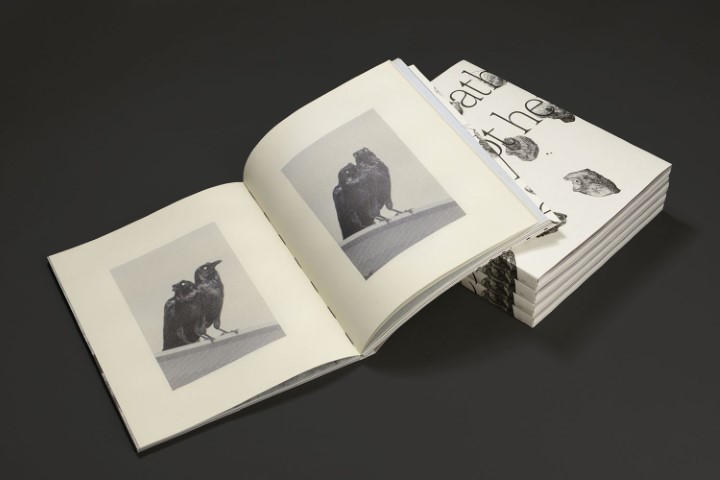

Le thème des périphéries entre la vie et la mort, et l’ancien et le présent, sont explorés plus loin dans la documentation en cours de Van de Voorde de corbeaux australiens. En 2018, à la suite d’un cadeau d’un téléscope, il a commencé à documenter les corbeaux australiens, obsédés par leur société aéroportée parallèle coexistant avec la société humaine. Dans de nombreuses cultures, le corbeau est considéré comme un médiateur entre la vie et la mort, parfois un mauvais présage de perte ou pour d’autres de prophétie et de perspicacité. Au début, Wouter Van de Voorde a photographié les corbeaux avec méfiance, les voyant comme de sinistres porteurs de mauvaises nouvelles. Mais, au fil du temps, sa perception des oiseaux s’est transformée en tendresse, alimentée par son privilège d’observer les moments de cette communauté de créatures magiques qui habitent notre monde et un autre au-delà.

Having studied painting before, Van de Voorde approaches lighting and photography with a painter’s eye. The monochrome images in this book were created on the lands of the Indigenous Ngunnawal people, the First Nation and Traditional Custodians of the Canberra, Australia, region.

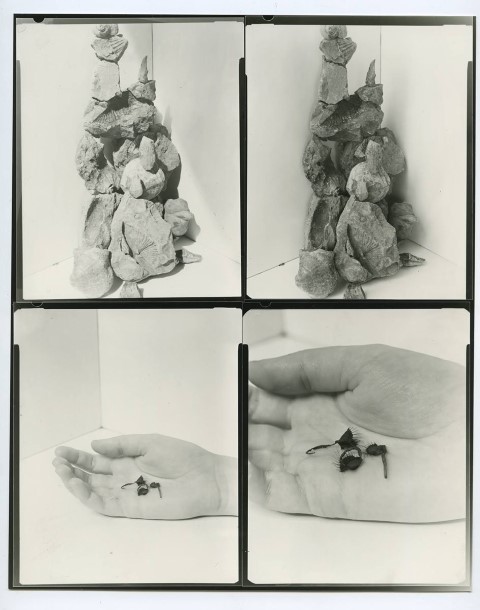

Against the backdrop of the pandemic, he was about to become a father for the second time. He had been making still lifes with fossils, and in his spare time he had begun digging in the backyard with his son unearthing the grave of a family chicken. Photographs of subsequent excavations, rock sculptures, an eroded gorge and an ongoing preoccupation with ravens are combined to create a new narrative representing everyday encounters between life and death.

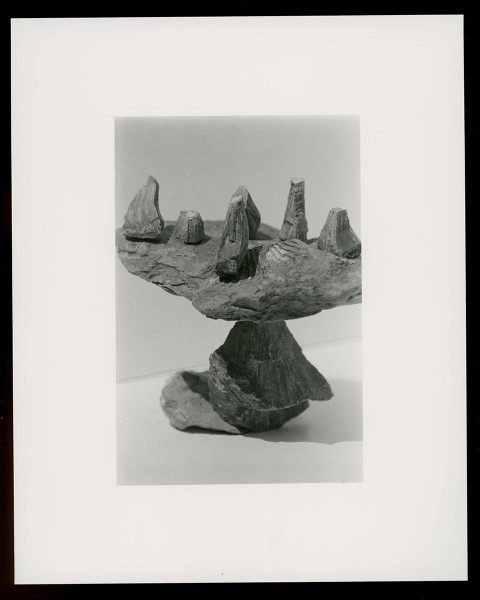

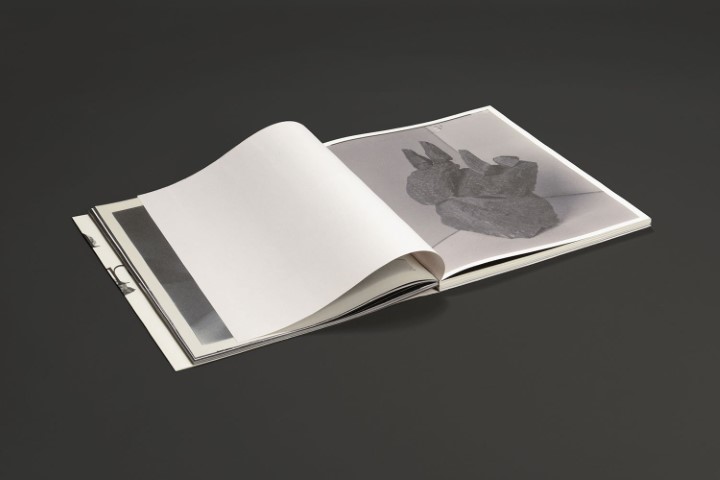

The book is punctuated with disquieting and ambiguous photographs of hand dug holes. The original impetus to create a hole was a request from Van de Voorde’s son to play real-life Minecraft and so they began digging in the backyard. As the hole grew deeper and wider, Van de Voorde became fascinated with the void and began experimenting with drawing the outlines of the holes with flames. Upon unearthing the grave of a departed chicken, the bones visible, they harvested clay and used to fire small objects, such as a skull pictured in the book. The images of the backyard voids are interspersed with photographs of the artist’s son exploring an eroded gorge, which appears like a giant version of their backyard excavations—father and son sharing explorations of what lies beneath.

Van de Voorde’s fossil collection, which features in the still lifes in the book, was driven by the excitement of the ‘hunt’—hammering large rocks to see what lay inside, buried for millions of years. The artist’s fascination revolves around the sheer age of the stones compared with the length of human life, the fossils’ permanence and the stack’s impermanence.

The theme of the peripheries between life and death, and ancient and the now, are explored further in Van de Voorde’s ongoing documentation of Australian ravens. In 2018, following a gift of a telescopic lens, he began documenting Australian ravens—obsessed by their parallel airborne society co-existing alongside the human one. Across many cultures, the raven is seen as a mediator between life and death, sometimes an ill omen of loss and others of prophecy and insight. At first, Van de Voorde photographed the ravens with caution, viewing them as ominous bringers of bad news. But, over time, his perceptions of the birds changed to a tenderness, fuelled by his privilege in observing moments of this community of magical creatures inhabiting both our world and another.