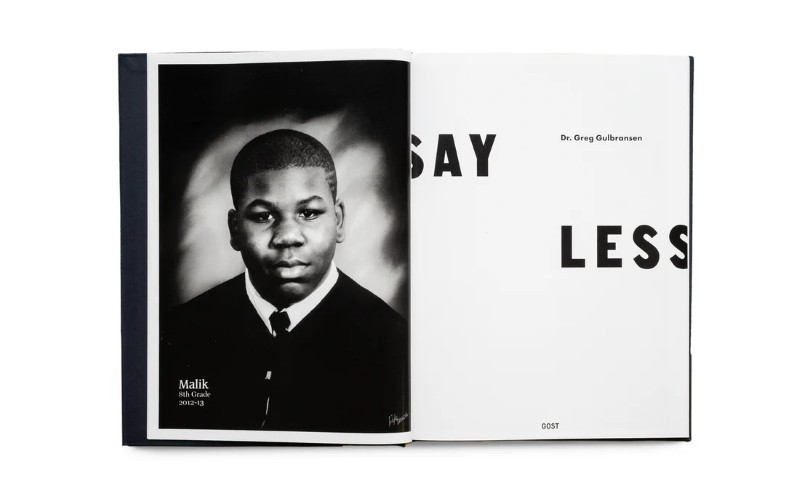

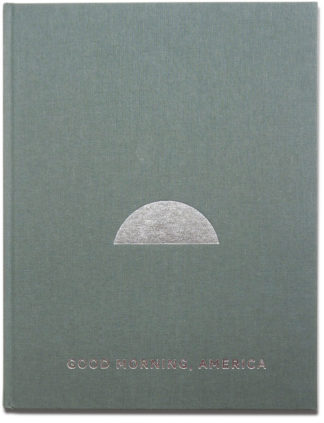

Gulbransen, un médecin pratiquant, avait photographié dans le Bronx pendant son temps libre et avait fait connaissance avec certains des enfants du coin. Il a commencé à remarquer beaucoup de jeunes hommes en fauteuil roulant avec des blessures à la colonne vertébrale et était professionnellement curieux. On lui a dit qu’ils avaient tous été abattus. Il voulait parler à quelqu’un en fauteuil roulant et a été présenté à Malik par l’intermédiaire d’un collègue du CRIP.

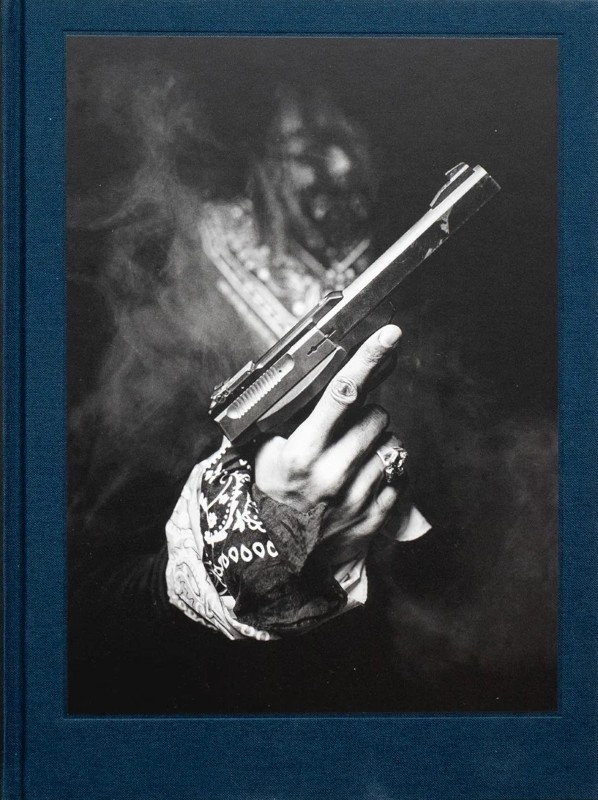

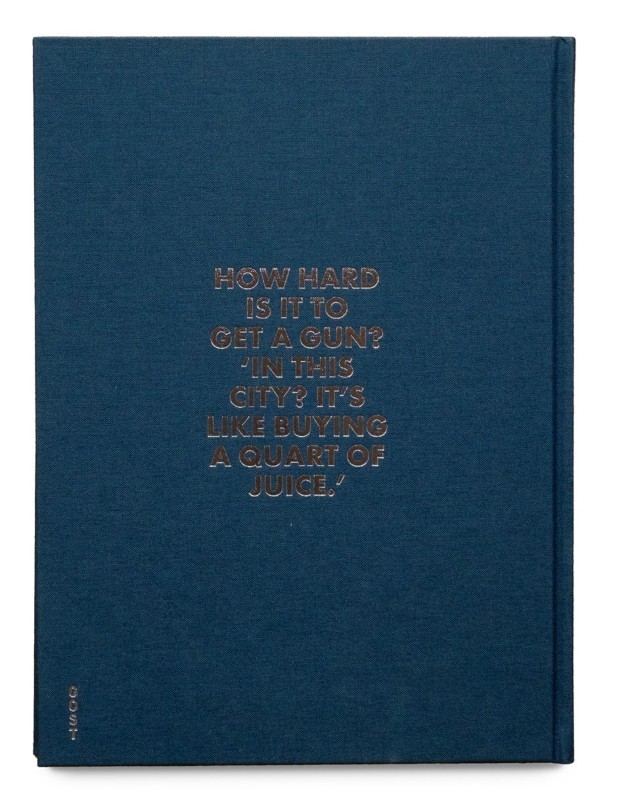

‘En tant que médecin, c’était une façon d’explorer un aspect de l’épidémie de violence armée dans ce pays. Il y a des fusillades tous les jours dans les cinq arrondissements de New York et le Bronx est le pire. Mais à travers le pays, la violence armée et la disponibilité des armes à feu est une urgence de santé publique. Les effets sont dévastateurs. Le médecin en moi veut montrer aux gens qui ne vivent pas dans des régions où les taux de violence armée sont élevés à quel point cela peut être terrible dans ces endroits, à quel point le problème est compliqué, La portée de l’épidémie de violence armée est très grande. Le photographe en moi essaie de montrer ce que c’est d’être victime de violence armée tout en faisant partie du problème.

Un soir d’été en 2018, Malik a quitté son appartement pour aller chercher un sandwich pour dîner. Il a été abattu devant une boutique à 99 cents par un gang rival. Les balles ont enflammé la colonne thoracique de Malik et l’ont instantanément paralysé de sa poitrine vers le bas. Malik était l’un des principaux leaders du gang local et, même après cette scène, les membres du gang continuaient de venir à son appartement à toute heure du jour et de la nuit pour parler, planifier et prendre soin de leur chef.

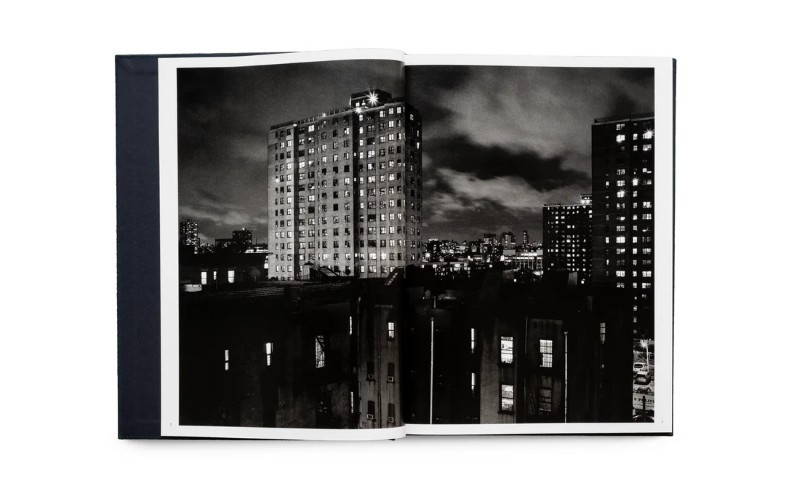

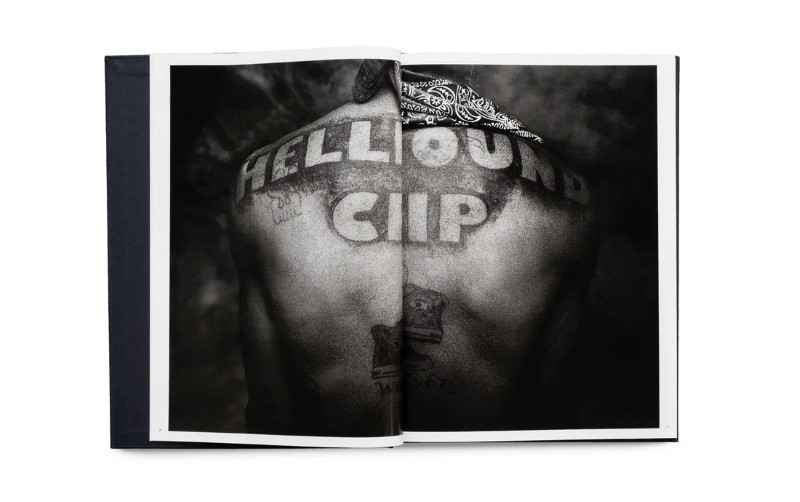

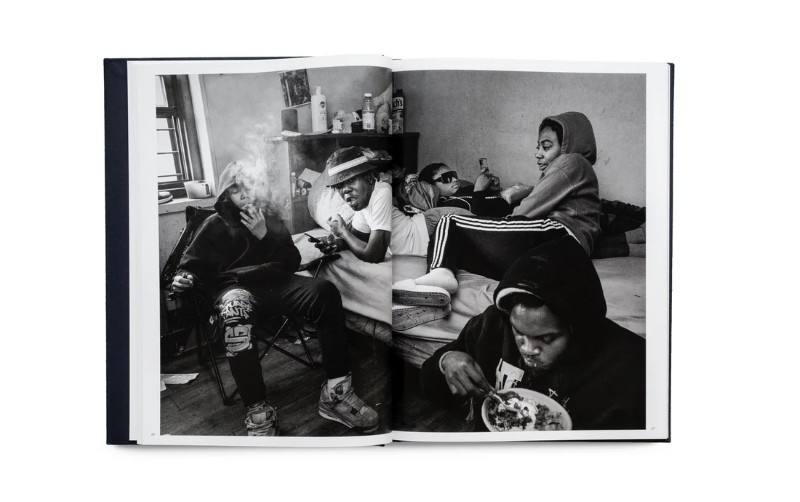

Malik vit avec sa mère et son grand-père dans un projet de logement. Il n’y a pas d’infirmières ni d’aides pour aider à soigner Malik, alors pendant la journée sa mère, Eyanna, gère ses nombreux problèmes médicaux comme changer sa couche et son cathéter, et son père est de garde la nuit. Les photographies du livre montrent la vie quotidienne de Malik : l’appartement exigu, les difficultés d’habiter et de se déplacer dans le petit espace en fauteuil roulant, les membres des gangs qui viennent visiter, les conversations silencieuses, la proximité et l’amour de sa famille, et la proximité de la violence et de la perte.

« C’est un espace très émotionnel. Il y a de la tension, de l’obscurité et de la peur. C’est un lieu d’agitation. Pourtant, en même temps, il y avait toujours tant d’amour et de soins. L’appartement était rempli de contradictions.»

À ce jour, Malik ne peut pas entrer dans certains quartiers, ni se déplacer dans certaines rues, ou il y a de fortes chances qu’un membre d’un gang rival essaie de le tuer. Son monde est sa chambre à coucher. Il est pris au piège.

« J’essaie de compliquer les choses pour les lecteurs en montrant, espérons-le, que juger des gens comme Malik pourrait être plus difficile, moralement parlant, qu’ils ne le pensent. Il y a beaucoup de victimes ici et, oui, certains d’entre eux sont des auteurs, . Je ne dis pas que ces gens sont des saints — ils ont tous fait des choix et ils devraient être tenus pour responsables de leurs choix —, mais ce sont aussi des victimes.

Gulbransen, a practicing doctor, had been photographing in the Bronx during his spare time and had got to know some of the local kids. He began to notice a lot of young men in wheelchairs with spinal injuries and was professionally curious. He was told they had all been shot. He wanted to speak to someone in a wheelchair and was introduced to Malik through a fellow Crip.

‘As a physician, it was a way to explore one facet of the epidemic of gun violence in this country. There are shootings every day in the five boroughs of New York City and the Bronx is the worst. But across the country, gun violence and the availability of guns is a public health emergency. The effects are devastating. The physician in me wants to show people who don’t live in areas with high rates of gun violence how terrible it can be in these places, how complicated the problem is, how far-reaching the effects of the gun-violence epidemic are. The photographer in me is trying to show what it’s like to be a victim of gun violence while also being a part of the problem.’

One summer night in 2018, Malik left his apartment to pick up a sandwich for dinner. He was shot in front of a 99-cent store by a rival gang. The bullets evered Malik’s thoracic spine and instantly paralysed him from his chest down. Malik was one of the key leaders of the local set, and so, even after theshooting, gang members continued to come to his apartment at all hours of the day and night, to talk, plan and to take care of their leader.

Malik lives with his mother and grandfather in a housing project. There are no nurses nor aides to help with Malik’s care so during the day his mother, Eyanna, manages his many medical issues such as changing his diaper and catheter, and his father is on call at night. The photographs in the book show Malik’s day-to-day life—the cramped apartment, the difficulties of inhabiting and navigating the small space in a wheelchair, the visiting gang members, hushed conversations, the closeness and love of his family, and the proximity to violence and loss.

‘It’s a very emotional space. There’s tension there, darkness, fear. It’s a place of turmoil. Yet at the same time there was always so much love and caring. The apartment was filled with contradictions.’

To this day, Malik can’t enter certain neighbourhoods, travel down certain streets, or there’s a good chance a rival gang member will try to kill him. His world is his bedroom. He is trapped.

‘I’m trying to complicate things for readers by hopefully showing that passing judgment on people like Malik might be more difficult, morally speaking, than they think. There are a lot of victims here and, yes, some of them are perpetrators, too. I’m definitely not saying these guys are saints—they’ve all made choices and they should absolutely be held accountable for those choices—but they’re victims, too.’